|

1912

The star of the lost generation

Huw Richards

July 10, 2012

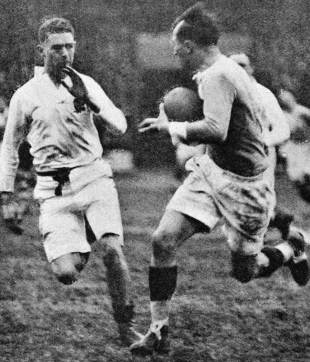

It was an era when many rugby players never got a chance to shine due to the two World Wars - here Adolphe Jaureguy runs at the English defence

© PA Photos

Enlarge

Max Rousie was unlucky in the single fact over which any rugby player has least control, his date of birth. There have possibly been worse years than 1912 for an ambitious French rugby union player to be born - some of those dates in the 1890s which made it highly likely that any career would be truncated by service and possibly death on the western front come to mind - but not many. Any Frenchman born 100 years ago would not yet have been out of his teens when his country was expelled from the Five Nations, spent most of the 1930s with a single annual match against Germany as the sole international open to him, then followed up with war, invasion, Nazi occupation and the resumption of normal international rugby only when he was well into middle age. Well might several French chroniclers have labelled them 'the lost generation'. Not the least of the achievements of Rousie, a butcher's son born in Marmande 100 years ago this month on July 18 1912, was that he managed to win a Five Nations cap before France's expulsion. A prodigy who also excelled at athletics, diving and Greco-Roman wrestling, he played his first senior match for Villeneuve-sur-Lot at 15 and was less than 18 and a half when he became the first international player produced by his club, against Scotland at Murrayfield in January 1931. Scotland won 6-4 in a match of which it was written that 'long before the end, the players seemed as bored as the spectators' and Lucien Serin - France's established scrum-half of the time - was recalled for their final Six Nations matches before the schism. Rousie was to play three more times for France against Germany - scoring two tries in the 1931 match at Stade Colombes - and rapidly established himself as the brightest star in the French game. Henri Garcia recalled that: 'He had every talent a rugby player might wish for: as powerful (1m78, 83kg) as a forward, he was a marvellous attacker, clutching the ball in his huge hands and evading defenders with remarkable ease. A fearsome tackler, he was also a masterly kicker, with one effort measured at 58 metres. He combined in himself rugby a both its toughest and its most radiant'. With talent like that, he was inevitably a target for rugby league as the rival code took advantage of French union's isolation to offer players a sport in which they could both be paid openly and play internationally for their country. It is possible he went a little reluctantly. Jean Galia, the entrepreneurial former union star who was league's driving force and recruiting officer, had been a team-mate at Villeneuve and so well aware of Rousie's singular gifts and crowd-pulling qualities, but he was not among the very earliest Treizistes, recruited in 1933. But within a year Rousie had changed codes, making an immediate impact with a long-range try on his debut in May 1934 against a Leeds team thinly disguised as a Yorkshire select, and still more on six-match autumn tour of England where he scored 12 tries and 20 goals in six matches without ever being on the winning side. He scored four tries against Broughton Rangers and against Leeds "from a scrum on the Leeds 25, he passed to stand-off Cougnenc, ran around him to take the return pass and accelerated unstoppably towards the line". His inevitable debut for France came against England in Paris on March 28 1935. Australian journalist Harry Sunderland reported that he was "a revelation. He scored a try after running right from his own 25 and sidestepped around Jim Brough as though the Englishman was not there". As Mike Rylance records in The Forbidden Game, Rousie 'unfailingly left his mark on every game he played in'. He won championships with Villeneuve in 1935 and Roanne in 1939 and was an ever-present in the French national team, succeeding Galia as captain. In 1937, playing against England at Halifax, he drop-kicked a goal from the angle of halfway and the touchline and two years later, playing at fullback, led France to victory over England in England - a feat unmatched by the union team in 10 attempts between 1906 and 1930.

Boxer Marcel Cerdan (right) was a great friend of Max Rousie

© PA Photos

Enlarge

Rene Verdier wrote of him as "the idol, the god of the stadium, whom thousands of youths dreamed of emulating" while his team-mate Ernest Camo, another of union's lost generation, remembered that "his name on the team-sheet was sufficient to guarantee a big crowd". In 1940 Rousie fought sufficiently bravely during the German invasion to be decorated with the Croix de Guerre. Rylance records that "He never settled into a single position. There was something of that in his personal life as well". Rousie enjoyed celebrity and the friendship of stars like singer Edith Piaf and boxer Marcel Cerdan, but struggled after the war with alcoholism, a battle he appeared to be winning before he was killed in a car crash on June 2 1959. Rousie's contribution to both codes makes him, as Thomas Mankowksi of Sud-Ouest wrote earlier in this centenary year, 'the only man capable of reconciling the Capulets and the Montagus of French rugby'. He has been commemorated since 1960 in the naming of the trophy awarded to France's rugby league champions, more recently by stadiums in Paris and Villeneuve, and in the memories of those old enough to have seen him. Jean Lacouture, whose recall goes back to the 1930s, described him two years ago as 'incomparable', while Garcia in 1973 wrote that "those who saw him play reckon him the greatest of all French rugby men". © ESPN Sports Media Ltd.

|

Live Sports

Communication error please reload the page.

-

Football

-

Cricket

-

Rugby

-

- Days

- Hrs

- Mins

- Secs

F1 - Abu Dhabi GP

Abu Dhabi Grand Prix December 11-131. Max Verstappen ()

2. Valtteri Bottas (Mercedes)

3. Lewis Hamilton (Mercedes)

4. Alexander Albon ()

5. Lando Norris ()

6. Carlos Sainz Jr ()

-

ESPNOtherLive >>

Boxing - Nelson v Wilson; Simmons v Dickinson; Joshua v Gavern (Metro Radio Arena, Newcastle)

Golf - Houston Open

Snooker - China Open

Tennis - Miami Open