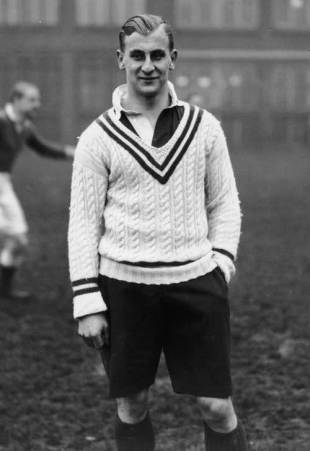

Alexander Obolensky played only four matches for England, in a single season, yet his name adorns a Twickenham hospitality suite and there are plans for a statue in Ipswich. Among pre-war England players only Wavell Wakefield, similarly honoured at Twickenham, remotely rivals his continuing fame.

No man has become more famous on the basis of a single match, England's victory over New Zealand in 1936. The legend established by his two tries on his international debut that afternoon is enhanced by an improbable life and early death.He was born 100 years ago on February 17, 1916.

Obolensky was still awaiting naturalization as a British citizen when he was chosen for England. This led to a memorable exchange with the guest of honour, the Prince of Wales - very shortly to become Edward VIII and enjoy a reign little longer than Obolensky's international career. Introduced to the newcomer, the Prince asked 'By what right do you presume to play for England?'. Not the slightest discomposed, Obolensky responded with icy hauteur 'I attend Oxford University… sir'.

He was of course the only person at Twickenham that day who probably considered himself the Prince of Wales's social equal. He was a prince himself - although he was to request that he no longer be referred to as such when his naturalisation came through a few days after the match - scion of a Russian family whose antique nobility made the House of Windsor look like comparative upstarts.

He had been born in Petrograd (now St Petersburg) in 1916, escaped revolutionary Russia as a small child and received an English education at Trent College, where he learnt to play rugby and used his extraordinary pace to score 49 tries in one season.

Going up to Oxford in 1934, he won a blue in his second year, saving a 0-0 draw by crossing the field to haul down a Cambridge winger headed for the far corner.

Varsity matches were de facto international trials in those days, and that tackle helped propel him into the England team to play New Zealand a few weeks later.

That penchant for coming in off his own wing served him against the All Blacks. He had already scored one try, a superb but orthodox outside break past the full-back, when he received a pass on the right wing and cut back to run at an angle across the field and cross in the opposite corner. The New Zealand writer Spiro Zavos has argued that it was the sheer unorthodoxy of it that undid his countrymen, conditioned to believe that rugby is conducted along strictly logical lines!

England won 13-0 - their first, and still largest, win over New Zealand and the only British defeat outside Wales of any All Black touring team before 1972. A further reason for Obolensky's fame was that, unlike most earlier rugby highlights, his tries were captured on film and seen by a much wider audience than the capacity crowd at Twickenham.

In the short-term, though, this may not have helped him. Vivian Jenkins, Wales's fullback, sat through several hour-long cycles of cartoons and newsreels in a London cinema to make sure he had fully understood Obolensky's methods. He received only one pass when England played Wales at Swansea and Jenkins, forewarned by his pioneering video analysis session, tackled him into one of the piles of straw that had been cleared from the pitch.

| "Obolensky recognised the importance of his pace - he was once timed at 10.6 seconds for 100 yards - and spent hours in Elmer Cotton's sports shop in Oxford looking for ways of producing ever-lighter boots." | ||

After two further matches Obolensky, not helped by missing the 1936 Varsity match through injury, was dropped. It can be argued that the wing of real quality playing for England against New Zealand was Hal Sever who went on to score five tries in 10 internationals - a good rate in the low-scoring thirties - and lived on into his nineties. Townsend Collins, the leading Welsh critic of the time, certainly thought so, rating Sever the most impressive wing of the 1930s. But it is Obolensky who is remembered as, in the words of his Daily Telegraph obituary, "A romantic figure capable of doing almost incredible things."

Jenkins recalled, "He wasn't a great rugby player, but he was strong and a very fast runner". Obolensky recognised the importance of his pace - he was once timed at 10.6 seconds for 100 yards - and spent hours in Elmer Cotton's sports shop in Oxford looking for ways of producing ever-lighter boots, often so flimsy that they did not last a full match. Whether his speed was aided by consuming a dozen oysters before important matches is a matter for conjecture.

He wasn't the world's greatest student, emerging in 1938 with a fourth class degree - a grade since abolished - although certainly more successful than an earlier sporting student at Brasenose College, cricketer Ian Peebles, who left in 1930 after exam results summed up by his tutor, "You obtained one per cent on one paper and were not so successful in the other'.

There was, though, a serious-mindedness about him. He contributed an essay to a book called 'Oxford in Search of God'.In 1938 he joined the RAF Volunteer Reserve and was called up when war broke out a year later. The war also brought an unexpected upswing in a rugby career he had continued as a hugely popular figure at Rosslyn Park.

He was recalled by England, playing in the winning team in a charity international in Cardiff in early March 1940. He should have played in the return match at Gloucester at the end of the same month. Instead the match was preceded by a minute's silence.

The day before, Obolensky had crashed his plane on landing at Martlesham in Suffolk, becoming the first England player to die on active service in the Second World War , and sealing a romantic legend.

Huw Richards is qualified to play for either Wales or England and was only prevented from doing so by being slow, short-sighted, averse to pain and lacking in any compensating talent. Denied sporting success he became a journalist and, after contributing to the demise of several short-lived rugby magazines, was the FT's rugby writer between 1995 and 2009 and currently writes for the International Herald Tribune and the Sunday Herald.

Huw Richards is qualified to play for either Wales or England and was only prevented from doing so by being slow, short-sighted, averse to pain and lacking in any compensating talent. Denied sporting success he became a journalist and, after contributing to the demise of several short-lived rugby magazines, was the FT's rugby writer between 1995 and 2009 and currently writes for the International Herald Tribune and the Sunday Herald.

He has reported nearly 300 international matches, including all six World Cups. He co-wrote Robert Jones's autobiography and analysis of the Welsh game Raising the Dragon and is also the author of Dragons and All Blacks, which was short-listed for the William Hill prize and A Game for Hooligans: The History of Rugby Union. His latest book The Red and the White, a history of the England-Wales match, was published in 2009.

He lives in Walthamstow, writes on cricket for the International Herald Tribune and his other enthusiasms include Swansea City FC and rugby league.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed