- Premier League

The rise and fall of a football empire

Two years ago, Barcelona were competing to be the greatest club team of all time. Cruel fate's intervention means they have been forced to seek a new direction.

Judging by the war of words between their former coach and club president Sandro Rosell, the collective spirit that powered the Pep Guardiola years eventually came apart at the seams. Perhaps the pressure of flying so high was always going to cause a crash but Tito Vilanova's departure to battle against cancer is the type of unforeseen event that can throw a runaway train off its rails.

Gerardo Martino, a coach whose experience of European football extends to a single season spent as a player at Tenerife over two decades ago, has been given the task of reviving Barca. They are Spanish champions, of course, but a sense of primacy has gone, especially so after their thrashing by Bayern Munich in last season's Champions League semi-final.

Barcelona are experiencing the loosening of power that eventually happens to all great football dynasties. The descent from the top can take various courses.

Reaching the peak

Age is perhaps the greatest enemy of footballing success but success itself can be a destructive element too. In 1968, Manchester United achieved a dream in winning the European Cup. It was also the beginning of the end.

"I felt that after we won it, it seemed to me that everyone was saying: 'That's it, we've done what we set out to do'," George Best said in 1984. "I was 22. I wasn't going to reach my peak for another seven or eight years." Matt Busby's team faded fast, and with Bobby Charlton and Denis Law suffering the dying of their light, Best was left to carry an inferior team. Once Best had succumbed to the temptations of drink and female company, United crashed. Just six years after their glory night, they were relegated to the Second Division.

Brian Clough and his assistant manager, Peter Taylor, both spoke of the anti-climax of Nottingham Forest's second, successive, European Cup in 1980. They realised that a provincial club like Forest could climb no further. A round of disastrous transfer deals saw the pair fall out, irreparably in the end, and Forest set into decline once Clough's powers began to fade.

Meet the new boss

Clough is the prime example of an unwelcome new face hastening the decline of a superpower. Don Revie's Leeds United were ageing and careworn, but in 1974 Clough blazed into Elland Road with a opening salvo that mocked his new charges' years of success. He lasted an infamous 44 days, and though Leeds reached the European Cup final at the end of the 1974-75 season under Jimmy Armfield, the magic had gone. The family atmosphere that Revie husbanded at Leeds was shattered. Relegation beckoned by 1981.

When Giovanni Trapattoni parted company with Juventus in 1986, he had won six Italian titles and all three European trophies in ten years. Juve subsequently went nine years without a title. Trap's replacement, Rino Marchesi, won nothing, as the club made a series of disastrous signings that included Ian Rush from Liverpool. Trapattoni, meanwhile, was helping to revive Internazionale, winning the Scudetto and UEFA Cup with them.

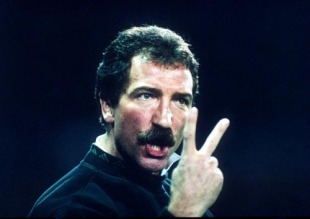

And though there had been signs of decline at Liverpool, the replacement of Kenny Dalglish with Graeme Souness in 1991 swiftly dragged the club down. A club that had dominated English football for nearly two decades became an also-ran to their rivals down the East Lancs Road.

"He never knocked Liverpool off their perch, that's nonsense that," Jamie Carragher said in 2010 of Sir Alex Ferguson's famous Manchester United mission statement. "It was Graeme Souness who did that, it really was."

Tragedy strikes

Manchester United's "Busby Babes" are the greatest unfulfilled story in English football. The death of eight of their players in the Munich Air Disaster of February 6, 1958, robbed the game of the "Flowers of Manchester" before they were ever fully in bloom. They already had two league titles to their name, and were on course for a domestic double, and perhaps that year's European Cup final. Their snowbound plane had crashed on the return from a quarter-final win in Belgrade, and it took United and Busby years to rise out from the ashes.

More devastating yet was the Superga crash of May 4, 1949. All Torino's players and coaches were wiped out when their plane crashed into a hill when trying to avoid a thunderstorm. Il Grande Torino had won six Italian titles in a row. Ten of their team made up the first-choice Italian national team. Torino were lost as a force to Italian football, probably forever: They have won only one championship - 1975-76 - since that fateful spring storm.

Too big for their boots

One of the trappings of success is the swelling of ego. Star players can become too hot to handle, too comfortable in their own skin. A downward spiral can result once players start having too much say in affairs. Martino's arrival at Barcelona from Newell's Old Boys seems to have come at the behest of Lionel Messi, a sign of the little man's ever-increasing dominance at Camp Nou. Warning: tracking the star system can be a recipe for disaster.

Johan Cruyff conducted the Ajax orchestra that dominated European football in the early 1970s, but eventually his overbearing ego brought about its downfall too. His love of money was infamous, such that coach Stefan Kovacs once rubbed a supposedly sore knee with a 1,000-guilder note. Cruyff then played on unhampered. Eventually, in the summer of 1973, the tantrums got too much, and a player vote for club captain deposed Cruyff.

Ajax were never the same after Cruyff flounced off for a big-money move to Barcelona, another club with a history of egos derailing a great team. Barca dominated Spanish football from 2004 onwards, and were 2006 Champions League winners over Arsenal in Paris, but by 2008 their spirit was gone. Ronaldinho was a flabby shadow of the former best player in the world, Deco was an ineffective malcontent, coach Frank Rijkaard had lost the dressing room. It took Pep Guardiola's revolution to begin the current cycle of success.

Movement of the people

A changing of the guard will usually signal the end of an era. It happens all too often to the less well-heeled. In the 1980s, Everton matched Liverpool punch for punch, but in 1987 their manager, Howard Kendall, was tempted to Athletic Bilbao, after Gary Lineker had been purchased by Barcelona the year before. Glasgow Rangers, then the richest club in Britain, robbed the Toffees of Trevor Steven and Gary Stevens. A similar wrecking ball was taken to Jose Mourinho's FC Porto after his team followed the 2003 UEFA Cup success with the Champions League in 2004.

Once Cruyff left Ajax, he was swiftly followed from Amsterdam by team-mates. Among others, Johan Neeskens joined Cruyff at Barcelona, Gerrie Muhren also went Spanish with Real Betis, as did Johnny Rep at Valencia. Ajax did not credibly compete for the European Cup for two decades before history then repeated itself.

New European Union transfer rules after 1995's landmark Jean-Marc Bosman ruling cost Ajax almost an entire team. By the time they kicked off the 1997-98 season, the group that had reached two consecutive Champions League finals was almost unrecognisable from the squad that took the 1995 title from AC Milan in Vienna. The likes of Edgar Davids, Patrick Kluivert and Clarence Seedorf were playing in Italy, and coach Louis Van Gaal had taken the De Boer twins to Barcelona.

Such an exodus is unlikely from cash-rich Barcelona but the club finds itself in a new era. History dictates that events will eventually effect decline.

John Brewin is a senior editor of ESPN FC where this article first appeared