- Rewind to 1969

The success before the banner

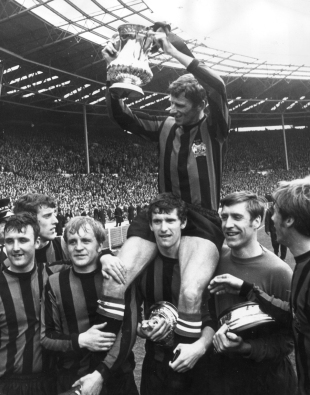

On Saturday, Manchester City face Stoke City in the FA Cup final at Wembley. It is 42 years since they last lifted the trophy thanks to Neil Young's solitary goal against Leicester City in the 1969 final.

As the scoreboard flickered to display 24 minutes in an FA Cup third-round tie against Leicester City in January of this year, Manchester City fans turned their backs on the action unfolding, apparently and strangely indifferent to a game that had just witnessed an equaliser from James Milner. Their necks, too, were incongruous, adorned as they were by scarves of red and black, traditionally the colours of the hated Manchester United, and not the sky blue associated with City.

This touching display was a tribute to Neil Young, who had been diagnosed with terminal cancer, and in recognition of his goal in the 24th minute of the FA Cup final of 1969 against the same opposition. Less than a month later, Young lost his battle against the disease, and this sad loss has imbued City's FA Cup challenge with added significance ahead of Saturday's final.

Though Mike Summerbee, Francis Lee and Colin Bell are perhaps more celebrated figures, few can rival Young's contribution to the greatest period in the club's history. He was top scorer when they won the league in 1967-68 and claimed a goal in the Cup Winners' Cup final win of 1970, but it is his feat in the intervening year that dictates he will always be remembered as a legend. Memories of Young will abound on Saturday as City seek to lift the trophy for the first time since his shot beat Peter Shilton at Wembley.

Thanks to manager Joe Mercer, City approached that match at the peak of the English game having only recently spent three years in the second tier. Mercer, in conjunction with his flamboyant and talented assistant Malcolm Allison, won promotion to the First Division in 1966 and within two years had installed City as champions of England; Young scoring twice on the final day of the season in a 4-3 win over Newcastle as City beat rivals Manchester United to the title by just two points.

The defence of their league title would prove problematic though, as the club finished the 1968-69 season in 13th place. A team that, according to Mercer, "took people by storm, or perhaps I should say surprise" with their daring, attacking approach the previous season, had been found out to an extent, their defence targeted. With league exertions proving tiresome, City instead found success in the FA Cup after their European Cup campaign was ended in the first round by Fenerbahce. According to Mercer, it had been "a mixed sort of season ... just the kind of season you do win the cup in."

It certainly looked that way, with defeats of Luton Town, Newcastle United, Blackburn Rovers and Tottenham Hotspur ensuring that, by the end of March, City were preparing for a semi-final against Everton, the team that would finish third in the table that season and boasted the midfield 'Holy Trinity' of Alan Ball, Colin Harvey and Howard Kendall.

City, of course, had their own collection of famous attacking talents, with Young prominent amongst them. Having finished as the club's top scorer with 19 goals in the title season, the Fallowfield-born childhood City supporter, who joined the club as an apprentice in 1959, continued his impressive form in the 1968-69 season and talk of an international call-up grew after he played a starring role in a 7-0 defeat of Burnley in front of England boss Sir Alf Ramsey. Despite finishing his career at City with a record of 107 goals in 412 games, international recognition was never forthcoming, but the graceful inside-forward, known as 'Nelly', was a hero to City fans nonetheless, not least because of his contribution to the cup success of that season.

His moment would await him in the final though, and it was Tommy Booth who scored the only goal to defeat Everton. Equally important as Booth's goal had been a last-gasp tackle from captain Tony Book to prevent Ball from scoring. "I was a stride short," Book said. "I couldn't get there with my left foot but I got my right foot and my body behind the ball. Had he gone on, he would have scored and that would have been curtains for us".

Book's own story demands retelling, as his experience is something of an anachronism in the modern game. The defender, who grew up in India and had a spell with Frome Town on his CV, only entered league football at the age of 30 after Allison, as manager rather than assistant, brought Book with him from Bath to Plymouth. Subsequently arriving at City in 1966, he was such an obscure figure that, when attending the first game of England's World Cup campaign with Mercer that summer, his new manager introduced him to the curious press as his friend 'Tommy Smith', with the journalists in attendance missing out on a scoop.

He quickly became an imposing figure in City's defence though, and recovered from a serious ankle injury at the start of the 1968-69 season to return for the climax of the club's cup run. He would even be named the joint Footballer of the Year with Derby County's Dave Mackay. The Guardian, profiling City's captain in advance of the final against Leicester, wrote: "He proved conclusively that encroaching age was no deterrent to an active and successful life in first-class football. In a comparatively short span he has earned as much distinction and appreciation as some men have achieved with 15 years' start."

Even given Book's unexpected rise to prominence, though, it was clear where City's strengths lay. Allison - who later in his career would enjoy a reputation as a playboy with his fedora hats and cigars, and would be pictured in a bath at Crystal Palace with porn star Fiona Richmond - described in typically forthright fashion why City would win the final in his column in the Daily Express: "There are many reasons why I believe we will win at Wembley today. But chiefly there are five. My fantastic five. The whole forward line. In fact, I think the whole team has too much class for Leicester City."

He was referring to Young, winger Tony Coleman and the fantastic array of talents that were Summerbee, Bell and Lee. Totemic figures in the history of Manchester City, the latter three in particular were darlings of the Kippax and brought a style and swagger to the side that was widely envied. This perhaps explains why Mercer was so furious with the state of the Wembley turf prior to the final, saying: "I simply can't understand how Wembley has got into this condition in the last 12 months. It used to be a bowling green; now it is a cabbage patch." It was feared Leicester, who were fighting against relegation and would eventually lose that battle, would seek solace in the state of the surface and attempt to prevent City's stars from playing. Not a bit of it.

Allison, watching on from the stands having been hit with a touchline ban in October that ended up running for years after he abused a linesman, would no doubt have been surprised at the endeavour and quality shown by Leicester in the first half at Wembley. Allan 'Sniffer' Clarke, who would join Leeds United in the summer, was a constant menace, and Hugh McIlvanney wrote in his match report: "If Manchester take credit for their adherence to the Mercer-Allison creed of class first, last and always, Leicester can look back with pride to an afternoon on which they rose far above the standards that have dragged them sadly close to relegation."

However, the game was decided by Young in favour of City in the 24th minute. Summerbee, at his elusive and determined best, escaped the grasp of Alan Wollett - Young later said "I think he beat him about three times" - and cut the ball back for his team-mate, who met the ball at the penalty spot and drove his shot past Shilton. Though Leicester created numerous chances, with Andy Lochhead missing a clear opening, City held on to win their fourth FA Cup, and condemn their opponents to a fourth defeat in the final.

In the rapture of victory, Coleman went up to collect his medal from Princess Anne and said "give my regards to your mum and dad". Later, a BBC crew, led by broadcasting great David Coleman, attended the club's victory party at a London restaurant, capturing Summerbee requesting that his team-mates sign his matchday programme. Young was heard to tell Coleman: "[I feel] great David, great. I've had one or two drinks."

Book, an FA Cup winner at 34 years old, awoke with the trophy the next day, fully consummating his love affair with a game that took him to its bosom so late in life. Allison, though, was already plotting further conquests.

"Something big is coming to Manchester City," he said. "They call it greatness. Don't get me wrong. I say this with the pleasure and excitement of a coach who has suddenly seen the scope and depth of his men. It is not arrogance - though arrogance comes easy to me, especially when the champagne corks are exploding about my ears, and my back aches with the slaps of congratulations ... As I said to Joe Mercer when Tony Book lifted the cup: 'Boss, we have the foundation. Now let's build Nelson's Column'."

What happened next? City entered and won the Cup Winners' Cup the following season, with Young scoring in the final against Gornik Zabrze, and also secured the League Cup as Allison's hopes of further glory came to fruition. However, after he replaced Mercer as manager in 1971, City's success dried up until they won the 1976 League Cup, with Book installed as boss. It is the most recent piece of silverware in City's collection. Meanwhile, Young went on to play for Preston and Rochdale and died of cancer at the age of 66 in February 2011.

© ESPN Sports Media Ltd.