|

South Africa

The history of rugby in non-white South Africa

Firdose Moonda

June 24, 2015

Allister Coetzee: The SARU team "had a responsibility to fight for change ... we were standing for justice"

© Getty Images

Enlarge

If a man captains a team that never plays a game, is that man still allowed to consider himself a captain? Ask Allister Coetzee "Of course. It was the pinnacle. I was extremely proud of it." Coetzee was the last captain of the non-racial South African Rugby Union (SARU) team. They were selected from the best players who competed in the Rhodes Cup. They were issued green blazers with a Springbok emblem. They had an official team photograph. They never played an international game. SARU existed in direct opposition to the South African Rugby Board (SARB), the administration that oversaw white players only. The SARB team was selected from the best players in the Currie Cup. They were also issued green blazers with a Springbok emblem. They also had official team photographs. They played 104 matches between 1891 and 1989, in which time they were regarded as the official face of South African rugby. Representation is a tricky business in South Africa - a country scarred by a segregated past that left the majority of its citizens relegated to second-class status, legally. Everything from residential areas to entrances to buildings to public toilets was divided along racial lines, and the world was only allowed to see the white side. That view made it easy to forget that non-white people played sport just as they lived somewhere, entered buildings and used the toilet. Colonial sports such as rugby and cricket arrived in South Africa in the 1800s and became part of the communities through mission schools and quickly becoming part of the entire country's culture. Organised rugby in white communities began in 1875, when Hamiltons Rugby Club was founded in Green Point - where a spectacular 64,000 stadium was built for the 2010 FIFA World Cup. Non-white rugby was not far behind. Records are more difficult to find, but Dr Hendrik Snyders, a historian and the heritage manager of the current SARU, told ESPN that his research showed that four of the 10 oldest clubs in the country were formed in non-white communities; for him, that's one way of proving that non-white rugby is just as established as white rugby. Dr Snyders notes also that the South African Coloured Rugby Football Board (SACRFB) was formed in 1897, just eight year after the SARB and before some of the white provincial unions. The timeline documenting the formation of the various rugby unions in South Africa - and there were many - is among the many points of surprise at the Springbok Experience Museum, the first of its kind for any sport in South Africa. The museum opened its doors in November 2013 after nine months of careful curation led by Dr Snyders, who wanted to tell the whole story of the game.

Dr Snyders still gets a kick out of seeing the look on people's faces when they realise the history of non-white rugby stretches as far back as the history of white rugby. "This is the point where you see the confused looks," Snyders said at the display. "People look at the two timelines and start doing the calculations in their heads and they think, 'Hey, but this coloured board is quite old and the guys were playing rugby back then.' Not just any rugby, but serious provincial competition. The SACRFB had persuaded Cecil John Rhodes to provide the silverware for which they competed. Along with the Currie Cup, it sits in the museum, where all the trophies - those in use and those which are no longer contested - are housed. The trophies that are still handed over are given to the winners to keep for 24 hours before they are returned to the museum at Cape Town's V&A Waterfront. By doing that, Snyders aims to keep Springbok Experience relevant by ensuring it connects the history to the present and educates and entertains visitors. "We want to show people the things they don't know about rugby but also help them re-live the things they do know," he said.

Two nations became one when Nelson Mandela strode to the centre of the pitch in a Springboks jersey and shook hands with Francois Pienaar, and Oscar winner Morgan Freeman tell the emotional story of that cornerstone moment and what it meant to South Africa's healing process in The 16th Man. Watch The 16th Man in Australia on ESPN on June 24 at 7am (EST) and 11pm (EST), and on ESPN2 at 5pm (EST).

The Springbok Experience © Firdose Moonda

Enlarge

Video recordings of iconic matches such as the 1974 series against the British Lions sit opposite one of an interesting and little-known attempt by the SACRFB to tour New Zealand in the early 1900s. Dr Snyders explained that the coloured board had written to New Zealand's administrators asking if they could visit but New Zealand officials wrote back to the SARB asking for information about the SACRFB was. The SARB's response was that they "do not know those players and have no jurisdiction over them", and New Zealand therefor declined the request. "The face of South African rugby could have been completely different if New Zealand had accepted and the team had toured," Dr Snyders said. "Who knows what would have happened?" That question can be asked about much of South Africa's rugby history. Who knows what would have happened if the players of the SACRFB; those from the South African Bantu Rugby Board, a separate entity for black African players only; and the SARB had all played on an equal playing field? Who knows what would have happened had there not been sanctions on South Africa and had they been part of the 1987 World Cup? We do know that rugby was not the domain of one racial group, and that is a message Snyders and SARU wants to get across. The game was part of all sections of society, although it did not mean the same thing to them all. The SARB believed they owned rugby. An example: all boards in South Africa used the Springbok emblem, but SARB insisted the South African Bantu Rugby Board's team, who had by then been renamed the African Leopards, covered the Springbok on their jerseys when they played against the 1974 Lions side. A hastily positioned patch with an embroidered leopard was put in its place. For the SACRFB - renamed SARU in 1966 - sport was a political tool. They adopted the mantra "no normal sport in an abnormal society," as did other sporting codes that were acting as anti-Apartheid activists. SARU organised domestic competitions, in which players of all races could play, but the mantra meant they were opposed to any tours, outgoing or incoming, against South African teams that were defined along racial lines. As South Africa became more politicised, the international community supported what SARU stood for. The 1981 Springboks tour of New Zealand came under heavy criticism from New Zealanders, some of whom who did not want a team from Apartheid South Africa visiting their shores. Apart from protests at every game, which culminated in flour bombs during the Auckland Test, New Zealanders who did not support the tour presented the Springboks with the "Book of the Unwelcome" on their departure. The hefty volume contains (mostly polite) messages condemning the visit.

A protester in Washington DC made her views clear over South Africa's 1981 tour of New Zealand © Getty Images

Enlarge

"It's quite amazing that the team management brought it back with them, but they did," Dr Snyders said of the book that can now be paged through at the Springbok Experience museum. "Now we can see what other people thought of us at that time. The 1981 tour has been given a significant amount of space at the museum because of the enormous impact it had on the South African sports landscape, but it is an uncomfortable display. The ceiling is low and the walls are painted black to create a sense of unease, "to explain the dark days" as Dr Snyders puts it.

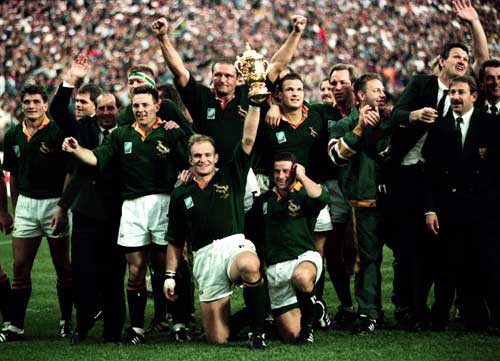

Nelson Mandela presents the World Cup to Francois Pienaar

© Getty Images

Enlarge

Immediately afterward, the pathway leads to the light. A golden glow glistens off the walls of the final passageway of the museum, which leads to the place where most people believe South African rugby was born: the World Cup of 1995. A sculpture of Francois Pienaar, Nelson Mandela and the William Webb Ellis trophy steals the gaze and the all the feelings of June 24, 1995, flood back. "Everybody loves this, because this is we won the world's hearts," Dr Snyders said. "And where we lost some of our memory." That historic day, about which Pienaar, in a 2003 interview with the BBC, said "no Hollywood scriptwriter could have written a better script" is what the world knows as South Africa's moment of unity. And in so doing, the world misses the understanding that it was but a moment; or a month of moments. A country that was little more than a year into democracy experienced euphoria when the Springboks were crowned world champions, but the cup was not a magic wand. It did not erase myriad problems in the country - it could never have been expected to do so - but it did not even address the sporting ones. Rugby was still a game trying to heal from division, and the years after the 1995 Rugby World Cup have highlighted that. There have been accusations of racial tensions simmering, and policies put in place to right the wrongs of the past that have only fuelled the tensions. But slowly, things are changing. More players who would have played for the SACRFB or SARU or the Bantu board - in other words, more non-white players - are coming through. And people such as Coetzee, who never had the opportunity to play for South Africa, could end up coaching them one day at Test level. He has enjoyed success with Western Province and the Stormers, and will now look to advance his career in Japan. Coetzee laughed when asked if he may come back to try for the Springboks job. "You never know." In South African sport, those three words mean more than uncertainty; they wonder what could have been. Does Coetzee wonder? "I suppose so. I would have loved to play against higher opposition but that wasn't possible. We had a responsibility to fight for change. We were not just a rugby team. We were standing for justice." Captain's words, whether his team played or not.

Two nations became one when Nelson Mandela strode to the centre of the pitch in a Springboks jersey and shook hands with Francois Pienaar, and Oscar winner Morgan Freeman tell the emotional story of that cornerstone moment and what it meant to South Africa's healing process in The 16th Man. Watch The 16th Man in Australia on ESPN on June 24 at 7am (EST) and 11pm (EST), and on ESPN2 at 5pm (EST).

South Africa celebrate with the Webb Ellis Cup, but the tournament was but a month of moments © Getty Images

Enlarge

© ESPN Sports Media Ltd

| |||||||||||||||

Live Sports

Communication error please reload the page.

-

Football

-

Cricket

-

Rugby

-

- Days

- Hrs

- Mins

- Secs

F1 - Abu Dhabi GP

Abu Dhabi Grand Prix December 11-131. Max Verstappen ()

2. Valtteri Bottas (Mercedes)

3. Lewis Hamilton (Mercedes)

4. Alexander Albon ()

5. Lando Norris ()

6. Carlos Sainz Jr ()

-

ESPNOtherLive >>

Golf - Houston Open

Snooker - China Open

Tennis - Miami Open