|

1963

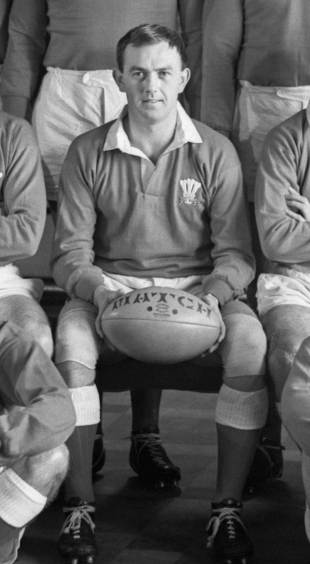

Rowlands puts the boot into Scotland

Huw Richards

February 19, 2013

Clive Rowlands dominated the match as his accurate kicking pinned back any notion of a Scottish attack

© PA Photos

Enlarge

Forecasting Six Nations rugby is a mug's game, but it can confidently be predicted that one feature of the Scotland versus Wales match played 50 years ago in 1963 will not be replicated when they meet at Murrayfield on March 9. No, not the Welsh victory or the 6-0 scoreline by which it was obtained, but the statistic for which the match has been remembered ever since, 111 line-outs. Given the elaborate process which goes into restarting the match from the touchline nowadays, it is possible that 111 line-outs would take up most or all of 80 minutes by themselves. Permanently associated with that number is Welsh captain and scrum-half Clive Rowlands. He has had one of the most impressive and varied rugby lives imaginable - 14 Welsh caps, all as captain, a hugely successful national coach, manager of Wales and the British & Irish Lions, a rugby politician whose career culminated in the presidency of the Welsh Rugby Union and a bilingual broadcaster. Yet, just as his future son-in-law Robert Jones is forever associated with his assault on Nick Farr-Jones during the 1989 Australia-Lions series and Clem Thomas went into history as the man whose cross-kick set up the try that beat the All Blacks in 1953, Rowlands is linked in perpetuity with Murrayfield 1963 and that extraordinary statistic. Some, notably Terry Godwin in his Five Nations history, have questioned it. But ESPNscrum's own John Griffiths point out that: "The game was very, very different then - lineouts were much more frequent and less formal than today, there was no restriction on kicking to touch from outside the 25-yard line and timing was at the whim of the refs - not terribly accurate." It is not the highest number ever recorded - there were reportedly 114 line-outs in the first ever match between New Zealand and South Africa at Dunedin in 1921. The radio commentary on the 1953 Wales-New Zealand match held by the New Zealand national sound archives records 75 in that match, including 17 in the first nine minutes, without this being regarded as worthy of comment. John Griffiths recalls that "For many years Vivian Jenkins of the Sunday Times used to bring a stats man along with him to the press boxes at all the big matches - I think his name was Tommy Thompson. Tommy's job was to count all the scrums, tight heads, lineouts, penalties etc. He was greatly trusted and many of Viv's colleagues clearly trusted his figures and faithfully reproduced them." It is those stats that, via the agency of Jenkins and his fellow-journalists, that have gone into the record. It was the second match for both teams. Scotland, with the aid of a massive forward effort, had beaten France, champions in three of the last four seasons with a share of the title in the other, in Paris while Wales had gone down to England on a Cardiff ice-field. The weather was brutal again, but the pitch playable thanks to a combination of Murrayfield's undersoil heating and the efforts of 35 shovel-wielders who cleared overnight snow. Snow wasn't the only thing that had happened overnight. Rowlands, reading the match programme, had realised that it had underestimated the weights of at least two of his forwards and what looked like parity was in fact a two stone advantage. This finding underpinned his decision to take Scotland on up front, and keep it tight. There were only two scores, a penalty by full-back Grahame Hodgson after 15 minutes in the first-half and a narrow-angled drop-goal by Rowlands, the only points of his international career and, as he readily admitted, something of a surprise after barely getting the ball off the ground in 20 attempted drops in practice the day before, 15 minutes after half-time. The Times reported that 'Not once in the match did the ball reach the centres direct from the stand-off". David Watkins, playing outside-half, had the perfectly reasonable alibi that he touched the ball only five times :"Once to collect the Scottish kick-off, twice to pick up their grub-kicks ahead, and twice only to catch passes from my scrum-half".

Nor did Scotland, until a belated flurry in the final quarter, play a more open game. Scotland were not starved of ball. Other statistics quoted in match reports show them winning 25 scrums to 13, including three to one against the head, and a far from disastrous 30 line-outs to Wales's 37, with 44 degenerating into mauls. Critics were unanimous in praising something else highly unlikely to be repeated on March 9 - a Welsh back row drawn entirely from small Gwent clubs - Haydn Morgan and Alun Pask of Abertillery alongside Ebbw Vale debutant Graham Jones. They were less united about Rowlands, who had been chaired off the pitch by exultant Welsh supporters (and snowballed by a few Scots while it was happening). His most vocal supporter was a neutral observer - Terry O'Connor of the Daily Mail, who hailed :"The greatest individual display I can remember in an international. He seemed to control every move of the match, even those of his Scottish opponents". Clem Thomas, in the Observer, struck a more analytical note, reckoning that Rowlands' "chip-kicking into the right-hand corner first exhausted the Scottish pack, then totally shattered their morale". But Michael Melford in the Telegraph reckoned that "What made the Welsh tactics completely incomprehensible to the simple neutral was that Rowlands had behind him a set of backs picked apparently for their lively qualities in attack", a complaint echoed by the less neutral Bleddyn Williams, captain the last time Wales had won at Murrayfield 10 years earlier. Rather like some of us when Wales won in Paris earlier this month, he perceived "A game completely without pattern or purpose, and the only real excitement came in the last 10 minutes". A still more critical view came from another Welsh critic, Dennis Busher of the Daily Herald, who reckoned the match exhibited "International rugby in its death throes as a spectator sport. Wales won by carrying 'modern' power rugby to its logical conclusion". Rowlands was cheerfully unrepentant :"No, I was never at any time tempted to open the game up and let my backs make the running. That's what Scotland were praying we'd do". The result did not, as Observer critic and former England captain Bert Toft, thought possible, lead to Wales battling out the title with France. This was to be England's year, and the victory served instead to save Wales from a first ever whitewash, but not the wooden spoon, when defeats against Ireland and France followed. It probably also saved Rowlands and a number of team-mates from an early end to their careers, paving the way for a shared title in 1964 and the Triple Crown year of 1965. Less fortunate was Brian Davies, one of those under-employed centres. It was the last of his three caps for Wales, possibly because of an incident recorded by the sympathising Bleddyn Williams in which he 'was so surprised to receive a pass that he dropped the ball as he was crossing the line'. Much as his brilliant near-contemporary Alec Murphy is credited with forcing a change in rugby league's scoring system with a hail of drop-goals, Rowlands has been seen as the begetter of the rule-change which in 1968 banned direct kicking to touch from outside the 25-yard line. As ever the story is a little more complex - Australia had been pressing for such a shift for years and been allowed to introduce it locally, hence its description at this time as 'the Australian dispensation'. It took five more years for the admittedly slow-moving wheels of the International Rugby Board to turn, and then only as an experiment, made permanent in 1970. But Rowlands, whose Wales teams were to exploit the freedoms offered by this and other liberating rule changes from the late 1960s with unmatched brilliance, certainly helped to grease those wheels. © ESPN Sports Media Ltd.

| |||||||||||||||

Live Sports

Communication error please reload the page.

-

Football

-

Cricket

-

Rugby

-

- Days

- Hrs

- Mins

- Secs

F1 - Abu Dhabi GP

Abu Dhabi Grand Prix December 11-131. Max Verstappen ()

2. Valtteri Bottas (Mercedes)

3. Lewis Hamilton (Mercedes)

4. Alexander Albon ()

5. Lando Norris ()

6. Carlos Sainz Jr ()

-

ESPNOtherLive >>

Snooker - China Open

Tennis - Miami Open