|

Rewind to 1864

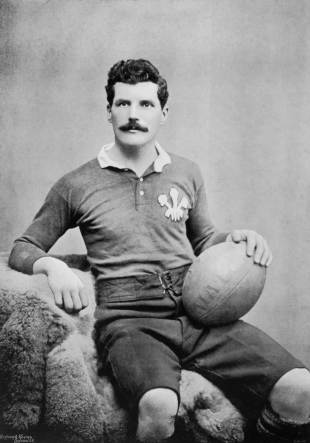

Arthur Gould: Welsh rugby's first superstar

Huw Richards

October 22, 2014

The great Arthur Gould

© PA Photos

Enlarge

Arthur Gould, who was born 150 years ago this month on October 10 1864, has a strong claim to be rugby's first authentic star. There were fine players before him, such as Lennard Stokes and Gregory Wade of England and the Scottish forwards Charles Reid and William McLagan. He had brilliant contemporaries like the Yorkshire centre Dickie Lockwood. None, though, could quite match Gould for achievement or charisma. He was both the beneficiary of, and a serious contributor to, the rapid rise of Welsh rugby from hapless newcomer in 1881 to Triple Crown winner in 1893 and the game's concurrent development there as a mass spectator sport. The final seal was placed upon his standing at the end of his career when he was the central figure in a controversy which split the game and might very easily have sent Wales off on a different trajectory. His fame, both during and after an career which lasted from his debut for Newport as an audacious 17 year old fullback in 1882 until 1898, was done no harm by having the most incisive, eloquent and durable chronicler of the early game - William Townsend Collins, otherwise known as Dromio of the South Wales Daily Argus - as a close and regular observer. Collins was to write in 1948:"In the early Nineties I thought Arthur Gould the greatest rugby footballer I had ever seen. Today after sixty years of football criticism I still think of him as the greatest player of all time." He was not, of course, a wholly objective witness. But his valuation, at least against Gould's contemporaries, had numerous echoes. The Yorkshireman Frank Marshall, whose Football : The Rugby Union Game is the game's ur-text, wrote of Gould in 1893 as "the central figure in the football world…the greatest centre-threequarter who has ever played". That Welsh rugby's first giant played for Newport was no fluke. The Welsh game's earliest years of prosperity belonged to the Black and Ambers as surely as the first Golden Age was owned by Swansea and the 1950s by Cardiff. They dominated early Welsh Cup competitions and were quick to develop fixtures against leading English clubs like Blackheath. Gould was of English descent - his father was a prosperous brass founder who moved from Oxford to Newport and produced a large family. Three of them - older brother Bob, Arthur and the slightly younger Bert - were to play for Wales, the first of only two such Welsh- capped trios. He was quick enough to be a nationally ranked track star, and gifted in other ways. Collins recalled that "Some boys, when they begin to play rugby football, find that they dodge, swerve and side-step naturally - it is not a question of thought, it is an animal instinct. Arthur Gould was one of them. He dodged or swerved away from a tackler instinctively." Raw talent was allied to hard work and incisive intelligence. As a teenager he observed with admiration Stokes' two-footed tactical kicking for Blackheath in a match at Rodney Parade, and practiced tirelessly to acquire the skill.

Collins wrote that "before he had gone far he had learned to study the capacity of his fellow players and the defensive powers of his opponents, knew what he was doing, why he did it, and how it was done." There was a playful element - his nickname of 'Monkey' came from a youthful passion for climbing trees which brought unexpected benefits at the 1887 Wales - England match, played at Llanelli, when the crossbar collapsed and Gould shinned up the posts to effect running repairs. That was when he was still a comparative newcomer to the Wales team. By 1889 he was captain, a post he retained when available - he missed the 1891 season on business in the West Indies - for all but one match between then and the end of his international career in 1897. His 27 matches for Wales were a record for any country at the time and only eclipsed in total by McLagan's 29, which included 26 matches for Scotland and three for the Lions. It was brother Bob's misfortune to lead a Wales team including Arthur to a shattering defeat by four goals and eight tries to nil against Scotland in 1887. That was the last of Bob's 10 matches for Wales, but Arthur was still around a year later when Wales beat the Scots for the first time. He was captain when Wales beat England for the first time at Dewsbury in 1890, confessing at the after-match dinner that he "had never felt as proud as he did that day" and again in 1893 when England were beaten for the first time in Wales - scoring a brilliant long distance try which Collins reckoned had 'as great a moral effect as any try ever scored' - and a first Championship and Triple Crown were completed. Alongside him at centre in the last two matches that season was younger brother Bert. Having a centre partner at all was still a comparative novelty. Arthur's career began when three threequarters - one centre and two wings - was the standard formation and while the shift to four was a Welsh innovation took some time to be convinced of its efficacy, not least because it had the potential to cramp his own very considerable style. Comparing Gould to Gwyn Nicholls, his successor as Wales's best and most charismatic centre, Collins reckoned Gould was "greater in individual skill" but Nicholls - a supreme midfield enabler of others - "was superior as an exponent of the four three-quarter system". Their Wales careers overlapped, just - the last three matches of Gould's career were the first three for Nicholls - who recalled from his times as an opponent in Cardiff v Newport matches that trying to thwart him was "like trying to catch a butterfly with a hat-pin", not least because "he was at top speed in two strides and away almost before one realised he was in possession of the ball".

The 1895 Wales team - Gould is third from the right in the second row

© PA Photos

Enlarge

By the time he played those matches alongside Nicholls, Gould had, as Dai Smith and Gareth Williams record in Fields of Praise "played in more first-class matches, scored more tries and dropped more goals than any other player on record". It was a record echoing another Victorian sportsman, the cricketer WG Grace, who - although an amateur - had in 1895 been the beneficiary of a huge, lucrative national testimonial campaign. It was Collins who drew the comparison and suggested that Wales might raise a similar testimonial for Gould. The idea snowballed rapidly and contributions flowed in, including one from the Welsh Football Union (as the WRU was then called). Unsurprisingly the Rugby Football Union, still seriously diminished by the Northern Union breakaway in 1895 and the still more conservative forces of the Scottish and Irish unions rapidly argued that this made Gould a professional. The WFU withdrew its contribution to the fund but otherwise dug its heels in, arguing that it - and not the RFU or other union - should determine who was regarded as a professional in Wales. In early 1897, shortly after Gould had played his last match for Wales - a 9-0 win over England at, suitably enough, Newport, the WFU resigned from the International Board. Its members, in an action which had a strong air of a Welsh-accented raspberry, voted Gould on to the union committee. There were no matches against Ireland and Scotland in 1897, while Anglo-Welsh club fixtures ceased. If Wales was isolated, the RFU found itself under siege. Midland and western clubs were angry at the loss of popular cross-border fixtures while the union itself, bent on strangling or at least confining the infant Northern Union, began to fear that if Wales were kept out it would join forces with the northerners. The WFU was not keen on the idea - leaders like union secretary Walter Rees, a Conservative councillor in Neath, were hardly fire breathing radicals and it cherished what were then the Home Internationals. But a long exile might have pushed it inexorably towards the Northern Union. The situation was made for a compromise, which was duly offered by the RFU. Its honorary secretary Rowland Hill, with ill-concealed distaste, persuaded the union to reverse its previous position and rule that Gould was still an amateur. Wales rejoined the IRB in 1898, with its autonomy over local issues of professionalism accepted, on condition that Gould - by now 33 and semi-retired, was not picked for any more internationals. Gould lived until 1919, his early death prompting a further subscription, to endow a bed in his name at Newport Infirmary. He lived on in the record books because of his 18 matches as captain. His mark was rapidly equalled, if Lions matches are included by the Scot Mark Morrison and then again in the first few years after the Second World War by Karl Mullen, captain of the 1950s Lions, but not beaten until France's Guy Basquet led his country in 24 matches between 1948 and 1952. He remained Wales' most capped centre until overtaken by Steve Fenwick in 1980, while his all-time record as Welsh captain lasted almost a century, until Ieuan Evans led Wales for the 19th time in a match of which Gould could scarcely have conceived - a World Cup qualifier against Portugal - in the summer of 1994. Other great players have followed, but a certain distinction always remains to the first. The writer Gwyn Thomas once complained that rugby took a disproportionate share of Welsh attention and energy because of its 'magnets of remembrance'. Few have been more magnetic, or more deservedly remembered, than Arthur Gould. © ESPN Sports Media Ltd

| |||||||||||||||

Live Sports

Communication error please reload the page.

-

Football

-

Cricket

-

Rugby

-

- Days

- Hrs

- Mins

- Secs

F1 - Abu Dhabi GP

Abu Dhabi Grand Prix December 11-131. Max Verstappen ()

2. Valtteri Bottas (Mercedes)

3. Lewis Hamilton (Mercedes)

4. Alexander Albon ()

5. Lando Norris ()

6. Carlos Sainz Jr ()

-

ESPNOtherLive >>

Darts - Premier League

Golf - Houston Open

Snooker - China Open

Tennis - Miami Open