- February 25 down the years

Clay takes title from Liston

1964

A chatty 22-year-old called Cassius Clay lived up to his boasts by winning the world heavyweight title. Sonny Liston was big and bad and apparently unbeatable. He hadn't lost a fight in ten years, grabbed the title by crushing poor Floyd Patterson in the first round, then did exactly the same in the return fight. But Clay was no midget himself. And he was infinitely lighter on his feet than plodding Sonny. No other heavyweight ever danced like he did. And his longer reach kept Liston at bay. By the end of the seventh, the champ's face was puffy and his shoulder was apparently damaged. He didn't come out for the eighth. The way the fight finished left a whiff in the air, but nothing compared with the terrible stench after the rematch on May 25, 1965. By then, Gaseous Cassius had changed his name to Muhammad Ali.

1994

Despite having her knee battered on January 6, Nancy Kerrigan made it to the Winter Olympics. So did her ice-skating rival Tonya Harding, who had a lot to do with the assault on Kerrigan's patella. But although the world's attention was on them, neither should have been regarded as favourite. At the 1992 Games, Kerrigan had finished third and Harding fourth, but in the meantime a 15-year-old Ukrainian called Oksana Baiul had won the world title. Here she followed Kerrigan onto the ice (Harding was tearfully out of contention after losing a lace on her boot). Kerrigan had skated an almost faultless free programme, but Baiul was more, well, beautiful. And her spins and footwork were superior, not immediately obvious to spectators who saw only jumps and their landings. Baiul won the gold medal by five votes to Kerrigan's four. Harding finished eighth.

1995

The tragedy that threatens every boxing match. Especially a boxing match between two big punchers. The fans love it and the magazines vote it fight of the year, but sometimes the price is a rip-off. Gerald McClellan was one of the greatest knockout punchers in history. He won the vacant WBO middleweight title by flattening the strong Ugandan John Mugabi three times in the first round. By the time he challenged another big hitter, Julian Jackson, for the WBC title, McClellan's last six fights had lasted a total of seven rounds. Jackson made it almost to the end of the fifth, then it was back to one round at a time for McClellan, including his last fight before today, against poor Jackson again. And the string of one-rounders looked set to continue when he went after Nigel Benn's WBC super-middleweight belt. Benn was well known as a puncher himself, but his defence was always a bit suspect, and McClellan simply blasted through it in the opening round, knocking him out of the ring. Benn got back in - and then we had a war. Bombs thrown from both sides, impending knockouts in every round. Benn was floored again in the eighth, but a short uppercut put McClellan down in the tenth. The punch wasn't particularly lethal, but McClellan looked as if he'd suddenly run out of gas. The long run of quick wins hadn't prepared him for anything longer (he rarely sparred more than eight rounds in training) and above all he'd had trouble making the weight. His trainer, the highly respected Emanuel Steward. might have pulled him out earlier, but they'd fallen out. McClellan knelt on the ring and stayed there while the referee counted him out. Then, as Benn and his team celebrated, McClellan began to slump on his stool. He fell into a coma and was left almost blind and deaf, partially paralysed, and severely brain-damaged, needing $70,000 of medical care every year. By 2007, he was able to stand upright again. Benn lost his title the following year and retired after two unsuccessful challenges.

1994

At the 1992 Winter Olympics, Norwegian ski-jumper Espen Bredesen had been one of the favourites on both hills. He finished 57th out of 59 on the big one and dead last on its smaller cousin. The Norwegian press dubbed him Espen the Eagle, after Britain's own Eddie Edwards. Two years later, in front of his own fans in Lillehammer, the pressure on Bredesen was horrendous. On February 20 he responded with an Olympic record on the large hill, but was beaten into second place. On the normal hill, he was second after the first jump, then set off towards the last-chance saloon. There are moments in a ski jump when you know it's gone on that second longer than normal, when you know the jumper has jumped the hill. Espen Bredesen jumped this hill and landed without a monkey on his back. From last to first in one of the great moments in any sport. Cue roar of home fans. Fairweather and otherwise.

1978

On the first day of the women's British Open squash tournament, the last British woman to win it lost in the first round. Fran Marshall was 47 by now, but maybe she thought the coast was clear at long last. She won the title back in 1961, then lost the next three finals to Australia's Heather Blundell. By the time Marshall reached the final again, in 1969, Blundell was now Heather McKay. She beat our Fran 9-2 9-0 9-0 and didn't lose a game in their four finals together. McKay won the title every year from Marshall's 1962 to 1977, a record that might have been even more unapproachable: she won the World Open in 1979.

1918

Bobby Riggs was born in Los Angeles. Famous for losing a match to Billie Jean King on September 20, 1973, he was 55 by then and it's hard to know what the match proved in tennis terms. But if it made people think harder about women's place in American society, it was worth all the pomp and silliness. Earlier on, he'd beaten Margaret Court, who was always nervous in big matches, but Billie Jean was made of different stuff. In his youth, Riggs had played tennis for real, and played it very well. When the great Don Budge turned pro after winning the Grand Slam in 1938, he left a vacuum in the men's game, and Riggs backed himself to fill it. Literally. It's said that he tried to bet on himself to win all three titles at Wimbledon in 1939 but no bookmaker took him seriously. So he had to make do with the glory. He won the doubles, beat his partner in the singles final, and took the mixed with Alice Marble, who also won the Triple Crown. In the same year, Riggs finished runner-up in the French and won the US. He lost in the final of the US the following year but regained the title in 1940. He was only 20 when he helped the USA win the Davis Cup in 1938.

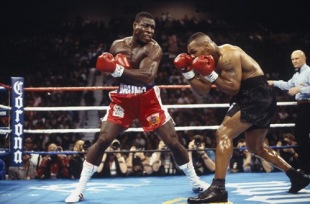

1989

Frank Bruno won a piece of the world title at last on September 2, 1995, but today was the closest he came to a real moment of glory. He lost that world title to Mike Tyson, then retired. Back here in 1989, he got his shot at Iron Mike on the strength of a win over a 37-year-old Joe Bugner, not the best credentials for taking on Tyson, who wasn't a shot fighter yet. This was the meanest man on the planet. Unbeaten in 36 pro fights, he was making the eighth defence of his various world titles - against a man known to have an iffy defence and weak chin. Sure enough, Bruno was down within the first 12 seconds, the result of a right hand followed by a forearm. No wonder big Frank spent the rest of the fight holding on for dear life. Tyson didn't get right through until the fifth round, then stopped the nonsense with two uppercuts and a right cross. But Bruno did have one moment, a shot at the title if you like, and it came in that first round. Shocked or not, he found a big left hook which went all the way down to the champion's legs That's all, folks. Just one punch. But it was enough to get Harry Carpenter excited in the TV booth. 'He's hurt Tyson! He's hurt Tyson!' That's as good as it got for the Iron One's opponents at the time. Best to remember him like that.

1956

Four days after breaking a world record that had lasted almost 20 years, Dawn Fraser broke one that survived more than 17. In her home town Sydney, she'd set a new world best for the 100 metres freestyle on February 21. In the same pool today, she swam the 200 free a second faster than the time recorded by the amazing Ragnhild Hveger in 1938. Fraser eventually set ten world records in the hundred and three in the two.

1889

Albin Stenroos was born in Finland. A patient man, Albinus. If at first you don't quite succeed... At the 1912 Olympics, he ran in the shadow of the mighty Hannes Kolehmainen, winning bronze behind the great man's gold in the 10,000 metres. He finished more than a minute behind, but others weren't even that good: only five runners completed the race. Stenroos came close to gold in the cross-country team event, Sweden beating Finland by a single point. But silver and bronze seemed to be all he was going to win. The War removed the 1916 Olympics from the calendar, and in 1920 Stenroos missed the Games and had to listen to how Kolehmainen won the Marathon. Inspired or envious or neither of the above, Stenroos had run his last Marathon in 1909. In 1924 he ran his next one, at Finland's Olympic trials. He was 35 by now, but that was the going rate for long-distance runners in those Olympics. Pouring it on over the last few miles, Stenroos finished nearly six minutes ahead of a 31-year-old Italian and a 36-year-old American. He set a world record at 20 kilometres and two at 30.