|

1925

The first red card

Huw Richards

May 6, 2011

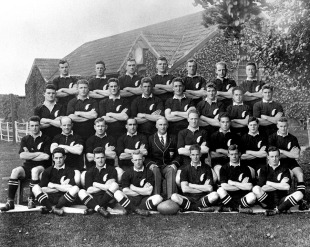

The New Zealand squad which toured Great Britain in 1925

© PA Photos

Enlarge

Reg Edwards, the Newport and England forward who died 60 years ago this week, has gone into history by an odd route - as the 'other man' in one of rugby union's most famous incidents. In January 1925 Edwards was chosen to play for England against the touring All Blacks at Twickenham. It was the tourists' final match in Britain and Ireland, one last supreme challenge as they pursued the 'invincibles' label that they have taken into history. England were reigning Five Nation champions on the basis of their Grand Slam in 1924 and, with Scotland declining to play the tourists following an administrative dispute, the toughest opposition the All Blacks were going to meet. The tension, in front of a huge crowd, was palpable and rapidly expressed itself in a series of ferocious brawls. Referee Albert Freethy issued two warnings then, after only eight minutes, ordered off All Black forward Cyril Brownlie. It was a huge moment. In more than 50 years of international rugby nobody had previously been sent off. Brownlie would retain his unwanted solo fame for the rest of his life - he died on May 7, 1954 - and a further 13 years afterwards, before another rugged All Black forward, Colin Meads, walked at Murrayfield in 1967. Terry McLean wrote of the fair-haired giant Brownlie that "in utter silence, he crossed the Twickenham pitch, the loneliest man in the world". New Zealand has officially forgiven Freethy, one of the outstanding referees of his time. The whistle he blew to restart the game after Brownlie's departure lies in the New Zealand Museum of Rugby at Palmerston North, although it leaves every four years to be used for the kick-off of each World Cup. But McLean, writing in 1959 recorded that his action was long resented by All Blacks. In 1937 Freethy came close to being assaulted in a Swansea bar by "a New Zealand cricketer who had also been an outstanding rugby player". Three members of that year's New Zealand cricket team were also All Blacks. McLean's choice of tense implies Curly Page, whose rugby career overlapped with Brownlie's but was long over by 1937 rather than the younger Eric Tindill and Bill Carson. Two members of the 1953-1954 All Blacks refused to walk a few yards to be introduced to him. New Zealand accounts of the incident argued that Brownlie was either wholly innocent or, at worst, guilty of retaliating after provocation. As McLean noted, "the variations in the accounts of the Brownlie incident were astonishing". One of the few consistent elements is that the opponent cited, or implied, as the provocateur is invariably Edwards. The New Zealand touch judge L.Simpson told a Wellington paper "Undoubtedly Edwards… was extremely lucky in not meeting the same fate as Brownlie". Arthur Carman, one of McLean's most distinguished predecessors among the New Zealand press, recalled that "Near the New Zealand line, Brownlie got the ball and dropped it, though Edwards then rushed him and grabbed at him, thinking Cyril still had it. The two struggled for a minute and then Edwards went flying over." Another New Zealand observer Read Masters does not name Edwards but blames the "excessive unpleasantness" of the early stages on "the over-keenness of one of England's forwards, who had also adopted illegal tactics in a previous game". If Edwards was indeed as guilty as Brownlie, the disparity in on-field punishment balanced out over the longer term. There was no further action against Brownlie. He played for the All Blacks the following week in Paris, and the week after in the international against France in Toulouse. The Toulouse game was his third, and last, full New Zealand cap. But he did play for the All Blacks again and will be recorded as having won a fourth cap in 1926 if New Zealand ever follows Australian practice in retrospectively upgrading matches played in the 1920s by the New South Wales Waratahs. He also went to South Africa in 1928 in the All Black party led by his younger brother Maurice, but had his chances limited by injury, and was a key figure in Hawkes Bay's Ranfurly Shield successes in the 1920s. Edwards stayed on the pitch at Twickenham, but McLean reports that he was "reported to the Rugby Football Union by Mr Freethy and it may have been only a coincidence that he was never again invited to play for England". It should also be pointed out that he was 32, so presumably on the down-slope of a first-class career that had begun 15 years earlier, but there are good reasons to believe that McLean's implication has substance. England had done extremely well with Edwards as a team member, winning Grand Slams in 1921 - when he played in all four matches - and in 1924, when he played three. The 17-11 defeat by New Zealand was only the second defeat in the 11 matches he played for England. The first had been in the famous mudbath at the Arms Park in 1922 when Wales scored eight tries, a result wholly out of keeping with an era of English success and Welsh weakness. Edwards - recorded by W.J.T.Collins as one of only three England players to emerge with credit from the debacle - would hardly have been human on that particular day had he not reflected that he really should have been playing for the other team. He was born in Pontypool and had played in several Welsh trials, but never progressed as far as selection. When England, still at this time wont to regard Newport players and the Monmouthshire-born as fair play - that it is a Welsh county would not be definitively fixed until the 1960s - saw their opportunity and chose him in 1921. Edwards played more than 200 times for the Black and Ambers either side of the First World War, was captain in 1923-1924 and 1924-1925 and a member of two of their most famous teams - the 'all-international XV' that played against Bristol in 1921, and included two other England players, Ernest Hammett and Robert Dibble, and the 'Invincibles' of 1922-1923. Collins, a perceptive and demanding critic said he was "not among the front rank of players" and was unimpressed by his captaincy. He was, though, clearly not a man to trifle with. Jim Brough, a member of the 1925 England team, told McLean that he was "a tough guy and a bit free with his fists", while England captain Wavell Wakefield recalled him laying out a Frenchman with a punch in 1924. Edwards appears to have been victim rather than perpetrator of provocation on that occasion, as toothmarks were clearly visible on his face. Like a similarly rugged later star of Welsh rugby, Clem Thomas, Edwards was a master butcher by trade, although there is no record of anyone saying of him - as Peter Robbins did of Clem - that he was "the only man allowed to practise his profession on the rugby field". Edwards had missed at least one prewar season visiting Canada before the First World War, and returned there permanently when his playing days were over. He died in Montreal on May 9, 1951. © ESPN Sports Media Ltd.

|

Live Sports

Communication error please reload the page.

-

Football

-

Cricket

-

Rugby

-

- Days

- Hrs

- Mins

- Secs

F1 - Abu Dhabi GP

Abu Dhabi Grand Prix December 11-131. Max Verstappen ()

2. Valtteri Bottas (Mercedes)

3. Lewis Hamilton (Mercedes)

4. Alexander Albon ()

5. Lando Norris ()

6. Carlos Sainz Jr ()

-

ESPNOtherLive >>

Snooker - China Open

Tennis - Miami Open