|

1938

'The most exciting thing seen in rugby for years'

Huw Richards

September 3, 2013

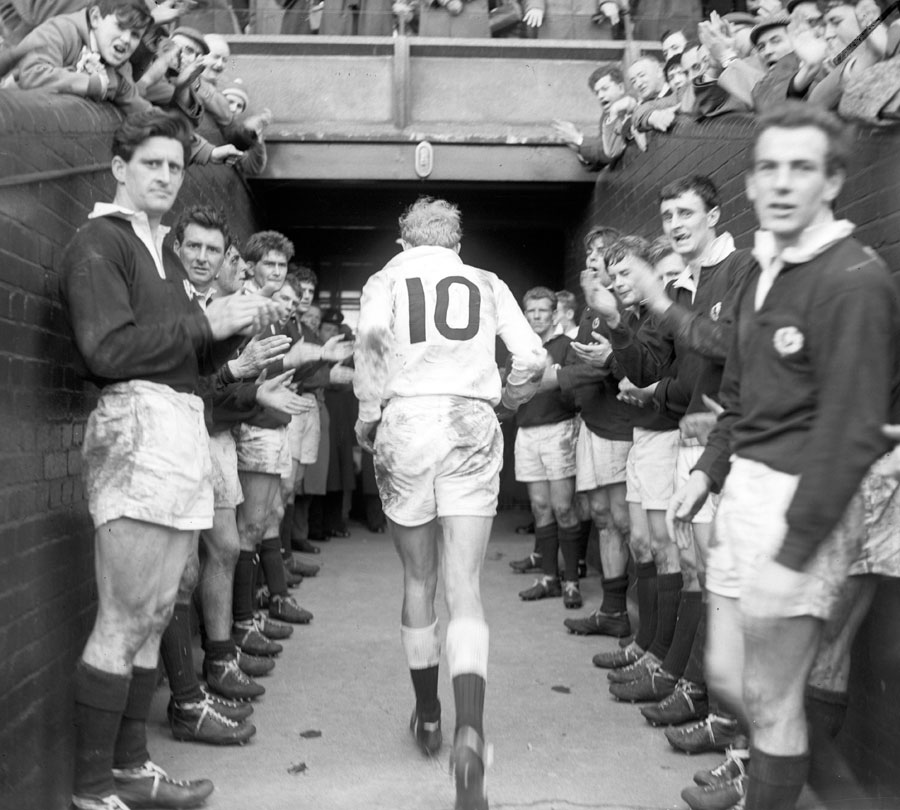

England's Richard Sharps heads to the dressing room having steered his side to victory over Scotland at Twickenham in 1962 © PA Photos

Enlarge

It's a very happy birthday to Richard Sharp, who will be 75 next Tuesday (September 9). News that the former England and Lions outside-half has reached that age occasions much the same sort of pang as that of Cliff Morgan's death. That old? Really? As well as epitomising a certain conception of Englishness - he was tall, blond, elegant and educated at public school (Blundell's) and Oxford, Sharp always had an air of youthful dash and panache. His career was a comparatively short one - 14 games for England and two for the Lions - but he left memories which far outweigh those numbers. Pre-Jonny Wilkinson (and occasionally since, if the compiler hankers after dash rather than pragmatism), he was always in with a shout when amateur selectors with sufficiently long memories were picking their all-time England XVs. Those memories focus on two spectacular displays at opposite ends of his England career. The times in between were not always so glorious. JBG Thomas wrote in 1966 of 'a career that tasted success and failure in equal measure' and that 'throughout his first-class career there raged a controversy as to his ability as an outside-half'. Cliff Morgan, who might be presumed to have known his outside-halves, felt that 'if Sharp had been a Welshman, he'd almost certainly have played in the centre because he was so unlike our idea of an outside-half. It would have given him extra time to think and turn into a truly great player'. There were, though, no such qualms following his debut for England in 1960. Sharp, while still only 21, had lived a fair amount - he had been born in India, at Bangalore, and did not come to Britain until he was eight. His university studies at Balliol College, Oxford had been prefaced by national service in the Royal Marines. He had also already played three times at Twickenham - twice for the Royal Navy and, a few weeks earlier, for Oxford. A decent Varsity match was often, in those days, a passport to an England cap, but Sharp owed his elevation to a mishap to a player from another academic institution, Bev Risman of Manchester University. Risman, son of rugby league legend Gus and a year older than Sharp, had played his way into the England team in 1959 and from there on to the Lions' tour of New Zealand, where his performances were highlighted by a brilliant solo score in the final Test. Even allowing for their notorious selectorial eccentricities, England were no likelier to pick another outside-half for the first match of the following season than Wales are to decide that Leigh Halfpenny is surplus to requirements when their next squad is selected.

Wales were also acutely aware of Risman. Geoff Windsor Lewis, their debutant centre, has recalled of the 1960 match: "At practice on Friday, the talk was of 'stop Risman'. Then Bev dropped out." Into the team came Sharp, in spite of that Twickenham experience almost as much an unknown quantity to some of his team-mates. Fullback Don Rutherford recalled that "I'd never heard of him and never seen him", before his call-up. A day later he was being hailed by Clem Thomas, whose sympathies as another Old Blundellian will have been outweighed by his more recent identity as Wales's captain until two years previously, as 'the most exciting thing seen in rugby for years'. Sharp's triumph was made possible by two of the more acute minds in English rugby. At the suggestion of flanker Peter Robbins, England's captain and scrum-half Dickie Jeeps made a couple of sharp, unexpected early breaks. England scored one early try through debutant wing Jim Roberts and Sharp's main marker, the usually formidable Abertillery flanker Haydn Morgan, already struggling with flu, was now left uncertain who to mark. The consequence was still vividly remembered by Windsor Lewis a half-century later: "England got the ball and we were supposed to go up hard, but Sharp went sailing through a huge gap and Roberts was in under the posts". England led 14-0 at the break, a colossal margin in those days. England went on to the title in 1960 and Sharp retained his place. Risman reappeared in 1961, then moved to centre as the selectors attempted unsuccessfully to accommodate both. While he had gone to rugby league by 1962, Sharp still faced the rivalry of Phil Horrocks-Taylor, who had been capped as early as 1958 and ended the season back in the team when Sharp was dropped after a hammering in Paris.

Richard Sharps clears his lines during a Five Nations clash with Wales in 1962

© PA Photos

Enlarge

Still, it was Sharp who went with the Lions in South Africa and like many a fine attacker before him found local conditions very much to his taste until he had his cheekbone fractured by a high tackle Springboks centre Mannetjies Roux. JBG Thomas thought that he was 'never quite the same' after this injury. Yet his greatest triumph was yet to come. Elevated to the England captaincy in 1963, he led them to a famous victory on an Arms Park icefield, followed by a 0-0 draw in Dublin and a 6-5 victory over France at Twickenham. The championship rested on the final match, against Scotland at Twickenham. The Scots, who had started brilliantly in a match where victory would have given them their first outright title since 1938, led 8-5 early in the second half when England were given the put-in at a scrum 40 yards out. They positioned wing Peter Jackson so that a blind side move seemed likely, but Jeeps fed Sharp moving wide of the Scottish cover. He performed a sumptuous dummy-scissors with centre Mike Weston then, as fullback Colin Blaikie closed in, dummied a pass to Roberts before sweeping past the wrong-footed fullback to the line. England fullback John Willcox converted and the rest of the match was scoreless, leaving England champions. Cliff Morgan was to write of it as "All grace, pace and coordination. For a fly-half watching a fly half, this try was the ultimate". Sharp was still only 24. Yet this moment of triumph was also, for practical purposes, the end of his international career. Now a teacher at Sherborne School, he could not get time off for England's first ever tour of New Zealand that summer, when the durable Horrocks-Taylor regained his place. Sharp played in that autumn's trials, but Horrocks-Taylor retained his place against Wilson Whineray's touring All Blacks while Sharp had a thoroughly unenjoyable afternoon in the Barbarians team hammered 36-3 by the tourists. When Horrocks-Taylor was discarded later in the season, England turned to yet another outside-half, the rugby league-destined Tom Brophy. With other commitments limiting his rugby - he had moved from Wasps to Bristol on taking up his post at Sherborne, but was to play fewer than 40 matches for them in four years - he had little hope of reclaiming his England place and announced his retirement from international rugby in 1965. There was one final, rather ill-advised coda when he was recalled as England's captain against the Australian tourists in early 1967. While this might look odd, it was the norm for an era that saw Johnny Williams recalled at scrum-half after a nine-year absence in 1965 and Gloucester lock Peter Ford, on his own admission 'a little over the top', given his first cap in 1964 following more than a decade of selectorial silence after a trial in Coronation Year. England went down 23-11 with Sharp described as 'a shadow of his former self' in The Times' match report. He retreated back to teaching, which in time gave way to writing for the Sunday Telegraph and a career in the China clay industry. Aside from the memories, and film of the 1963 try, was one more slightly unlikely legacy, in the writings of historical novelist Bernard Cornwell. Seeking a name for his military protagonist, Cornwell took his rugby hero and stuck an E on the end - Richard Sharpe. He proved even more durable than his near-namesake, featuring in 21 novels and a popular television series starring Sean Bean. It is far from unique for tribute acts to outlast their inspiration - as comedian Mitch Benn pointed out in his show at this year's Edinburgh fringe, the Bootleg Beatles have now been playing for four times as long as John, Paul, George and Ringo managed. But nor, in either case, is there any doubt about the quality of the original.

© ESPN Sports Media Ltd

| |||||||||||||||

Live Sports

Communication error please reload the page.

-

Football

-

Cricket

-

Rugby

-

- Days

- Hrs

- Mins

- Secs

F1 - Abu Dhabi GP

Abu Dhabi Grand Prix December 11-131. Max Verstappen ()

2. Valtteri Bottas (Mercedes)

3. Lewis Hamilton (Mercedes)

4. Alexander Albon ()

5. Lando Norris ()

6. Carlos Sainz Jr ()

-

ESPNOtherLive >>

Snooker - China Open

Tennis - Miami Open