|

Super Rugby

Greg Growden reflects on Super Rugby roller-coaster

Greg Growden

February 2, 2015

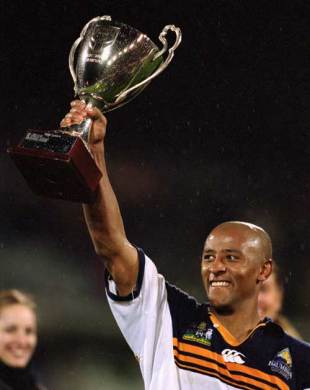

Michael Jones and the Auckland Blues dominated the first two seasons of Super 12

© Getty Images

Enlarge

Covering Super Rugby from day one has been a sometimes enriching, occasionally exasperating, most often mind-bending experience. Even being witness to the whole shebang's very difficult birth was rewarding - even if decidedly weird. Spending several months in South Africa can send you into a tailspin, especially when most of the time you're under virtual citizen's arrest, holed up in a D-grade chain hotel with its only redeeming feature being that it is on the other side of the road to a shopping centre. In such disconcerting surrounds, even scraping your fingernails across a chalkboard sounds like a sweet symphony. Due to the Wallabies' early exit from the 1995 Rugby World Cup, the Sydney Morning Herald team covering the tournament - Peter FitzSimons, photographic guru Tim Clayton and myself - were forced to spend weeks on end in one of those dreary chain hotels in Sandton, a business district then and now regarded as one of the few relatively safe places to stay in Johannesburg. We weren't a happy crew. Several of our laptops had fizzled out due to a hotel power surge - forcing us to spend hours on end every night reciting our stories to copytakers on the other side of the world. Hotel facilities were basic: lumpy bed, blocked toilet, cold tea, and dry toast not much else. With the hotel staff screeching at us of the dangers just outside the front door - car-jackings, murders, robberies, armed attacks on Tommy Tourists - you were virtually compelled into barricading yourself away in your tiny room, quivering under the threadbare blankets. To stop going completely bonkers, we had directed our attention towards the All Blacks, who were staying just down the road. But we discovered dealing with them made us even loopier. They treated all with contempt - not surprising considering their notoriously dour coach 'Lugubrious' Laurie Means thrived on paranoid behavior, especially when cornered by the international media. If any journalist succeeded in getting more than a monosyllabic answer from any of their players or officials, it was time for high-fives, much rejoicing and several hours at the bar. (It was only later that we discovered why the All Blacks were so edgy, as the hotel we had invaded was where the infamous Suzie the waitress supposedly poisoned them before the final. More unnecessary paranoia? Probably not.) There was only so much of Lugubrious Laurie we could take. Thankfully rugby intrigue distracted us, and gave us a reason not to plead insanity and bolt straight for Jo'burg Airport in search of a mercy flight home. At the time, the Australian rugby scene was in a state of flux: rugby league was at war, with the Super League saga bitterly dividing the 13-man game; and union was caught up in the mess, as Super League, desperate for talent, was hovering around the Wallabies in the hope of luring the best away. As the Wallabies headed to the World Cup in South Africa, the ARU was bracing itself to losing at least a dozen Wallabies to Super League. But there was an even more dangerous distraction. Several entrepreneurs were working away in the background, attempting to lure the world's best players to be part of a breakaway rugby union competition. World Rugby Corporation was rapidly gaining oxygen.

During the World Cup, WRC organisers had meetings with several Wallabies officials and players - getting an understanding from numerous key Australian rugby figures that they would sign up with the 'rebels'. Under enormous pressure to maintain control of the game, the rugby establishment finally had to react - working on a deal with Rupert Murdoch's News Corporation that would fund player salaries and allow the introduction of a Super 12 provincial series and a Tri Nations tournament. In the process, SANZAR was born. After the Herald, before and during the World Cup, had broken a series of stories on this new professional deal, FitzSimons and I were given a tip-off that we would get the whole story to ourselves if one of us went to a meeting with officials who had stitched up the deal. FitzSimons, who for some time had been on top of the story, knew one of the officials - Ian Frykberg, the former SMH journalist and international broadcast deal negotiator who died in 2014 - so he volunteered to go to the meeting. I would wait back at the hotel and, when he returned, would use his information to write a detailed article for the following day's Herald. Six hours later the boom boom boom of SMH's version of King Kong could be heard as he bounded down the hotel corridor. He walked through the door and began reciting the details. After an hour or so, I had pieced together from FitzSimons's observations and memories the details of the Super Rugby deal. His memory was perfect. Somehow FitzSimons' laptop was still working. So I was able to bang away on that for several hours before sending the story that announced the new era of rugby to the world. The following day came the official announcement that Murdoch had agreed to pay more than $US550million for the exclusive worldwide television rights to a triangular series, both at national and provincial level, between New Zealand, South Africa and Australia, for the next 10 years. And so the landscape changed. The WRC venture, which at one stage had the bulk of Wallabies and All Blacks signed up, eventually collapsed and, after several more extremely tense months, Australian rugby banded itself together to support the Super Rugby and Tri Nations ventures. Most importantly the punters took to it. The silly Super Rugby team names jarred right from the start, but the tournament was embraced because the structure was relatively simple to understand. Every team played each other, and the best from the south were involved. There was historical provincial rivalry involved. And in Australia, there were immediately tense border skirmishes. New South Wales and Queensland had been bickering away for decades, but the new kids - the ACT Brumbies - didn't take long to irritate their elders, particularly those who had long been in charge of operations in Sydney and Brisbane. The Brumbies relished being upstarts. Moulded around numerous rejects from NSW and Queensland who wanted to prove they had been wrongly neglected, the Brumbies thrived on and lived off a small town mentality whereby everyone else was perceived as enemies or were "just out to get them". They could also actually play with panache, and soon they created a far more harmonious team environment than the two larger Australian provinces. The Brumbies had the ideal first coach in Rod Macqueen; he was not as distrustful as Mains but wasn't that far behind. He cultivated an organisation that knew how to protect its own. They quickly turned into a secret handshake society, and beware anyone who tried to take them on. There was soon a divide between the Brumbies and the Sydney media. The Brumbies thought the spivs down the road unnecessarily gave them a hard time, and this tenuous relationship became even pricklier when Eddie Jones took over from Macqueen.

George Gregan and the Brumbies feasted on an us-against-them mentality

© Getty Images

Enlarge

Working for the SMH meant the Waratahs were your main rugby gig - and that prompted an endless stream of back-page stories as they were the masters of bungling virtually everything they touched. The Waratahs media round was like watching Marx Brothers movies on an endless loop - non-stop laughter due to constant acts of stupidity - both on and off the field. From an opening season when they airbrushed coach Chris Hawkins out of a team photograph, after he had been knifed by one of his staff members, to seeing another Waratahs coach forced to have his contract renegotiation interview with NSW Rugby Union officials in the dressing-room just before kick off at a home Super Rugby match, to inebriated Waratahs delegates lurching at you in the player tunnel, it got crazier and crazier as each season rolled on. It was certainly no surprise to me that it took until 2014 for the Waratahs to win the Super Rugby tournament. Talent is one thing - and for years the Waratahs had that in abundance - but intelligence was lacking, both in the football department and in front office. They were endlessly shackled. That's why it was always fun travelling overseas with the Waratahs. It was all a bit haphazard. It all sort of happened. And it all fell apart oh so often. Some of the highlights and lowlights included sighting the team playbook going round and round a South African airport terminal carousel, watching the team adapt during one Cape Town trip by using a towel wrapped inside a skullcap as a ball after they had forgotten to take any to a training session, and the weird looks at a Stellenbosch winery when the team one day arrived in fancy dress. Giving it all an edge was that you also had to keep a close eye on what they were up to in Canberra due to the interest in Sydney in the Brumbies. So for an escape from the lunacy otherwise known as Waratahland, there were numerous trips to Canberra Stadium - and the worst press box view in the world. They would either put you in a room at the far end of the ground where you couldn't see anything - as hundreds of spectators were either standing up in front of it - or the window would just fog up every time someone turned the kettle on at the back of the room. Even once I saw Mal Meninga underwhelmed with the view from where he was sitting in the Mal Meninga Stand.

Then down to the Brumbies dressing-room, which the locals treated like Fort Knox. This was the inner sanctum. It became more precarious when the Cape Town taxi affair occurred, as the relationship between the Sydney press and the Brumbies dissolved into nothing. Just sheer venom from either sides. The Brumbies did not take kindly that we wrote about how a group of players after a Super Rugby match had a very silly night out in Cape Town, which ended up with some damage to a local cab. The episode exposed inherent problems within a player-led organisation. And when the team returned home, it almost ended up in fisticuffs at Sydney Airport when Brumbies officials, who had lost all sense of decorum, decided the best way to divert blame was to slag off and provoke the messenger. These were no idle threats. Thankfully, the Sydney media kept its cool. Officials and several parents of Brumbies, meanwhile, did not help the scene as they attempted to inflame the moment with puerile remarks. We were now apparently the problem. So no surprise the Brumbies took great delight in trying to rub our noses in it when they won the Super Rugby title shortly after. "Well what do you think of us now?" came the dare at the Super Rugby victory press conference. "Not much" was the reply. Some years later, after leaving the claustrophobic Brumbies cocoon, Jones, now coaching the Wallabies, admitted to us long-time targets that he knew full well the rewards of inflaming a small town by looking for other scapegoats. And we were so convenient. So imagine the surprise when I was invited up on stage at Parliament House for a 2013 Brumbies player reunion to discuss old times while sitting next to so many of those Canberra players who had myself and several other newspaper colleagues high up on their 'hate list'. Cheshire cat grins always work in such situations. This was a fair stitch up; almost as good as being told by those higher up that it was a black-tie function, only to discover on arrival that I was the solitary person in the audience to turn up in the required garb. Yes I did look like an idiot up on stage, but what's new. There were also funny times when the Brumbies were around. One of the best occurred in Sydney when the Brumbies were once again fuming over something then Waratahs coach Bob Dwyer, a master agitator, had been sledging them about. So incensed were the Brumbies forwards, they made a pact to debilitate anyone in the Waratahs colours who got in their way. They did, and shoved around the NSW pack. But as a joke several of us in the press box decided to give the man-of-the-match award to Waratahs prop Matt Dunning. The looks on the Brumbies forwards, when Dunning's name was announced over the loudspeaker, was priceless. They all stopped, jaws agape. "What the ----," echoed around the ground. Gotcha.

Then again, as with the Parliament House function, two decades of covering Super Rugby has so often revolved around being quick on your feet. You had to be when accidentally ending up in a township after losing your way to Ellis Park, having to telephone copy through to the SMH copytakers from the lounge room of a New Plymouth house only to be booed by the family every time you mentioned the word "Waratahs", or trying to get more than a grunt out of a New Zealand player after they had lost. You also had to be prepared for anything, and that was certainly the case of the most memorable Super Rugby match I covered. Most games are forgotten within seconds of leaving the ground. Not the Waratahs debacle of 2002. Macabre admittedly, but more than a decade on I can vividly remember so much of what happened that night when the Waratahs decided not to take any risks just before finals time and suffered the consequences of a 96-19 shellacking in Christchurch.

The Crusaders had plenty to celebrate against the Waratahs in 2002 © Getty Images

Enlarge

That night was so bizarre it was sidesplitting. Even the hapless Waratahs, who spent most of the evening under their own goalposts trying not to break down in tears, eventually saw the humour in it. Those players included hooker Brendan Cannon, who was on the bench that night. At half-time, with the Waratahs long buried, Dwyer told his startled players: ''We're still in the game. We just need one or two things to go our way.'' In the second half, when Cannon took the field, he ran past the Crusaders bench and announced: ''There's 64 points in me.'' The next day when the Waratahs returned home, a cargo container was sighted through one of the aircraft windows. On one side the Christchurch airport cargo crew had written: ''Thanks for coming, Waratahs. Will you need a 100-point start against the Brumbies next week? You are the weakest link. Goodbye. Signed, the Crusaders.'' A week later in the semi-finals, the Brumbies won 51-10. A 100-point start would have been handy. As for my favourite Super Rugby game - again no argument. This I didn't attend, but the 2006 Super 14 final between the Crusaders and Hurricanes - again in Christchurch - wins out due to the exceptional television coverage. You couldn't see anything, but I would still rank it among my top five sporting event broadcasts.

An hour before kick-off, a thick fog covered the ground; it refused to lift, turning the match into something you would expect on a dark night in the Yorkshire Moors. Visibility was near zero. The players could see only a few metres in front of them. When Crusaders fullback Leon MacDonald arrived at the ground, he thought the fireworks had gone off early. And all the crowd could see were eerie shadows in the mist. The rumour soon spread that Lord Lucan was playing on the far wing. Those in the press box had given up after 15 minutes, demanding that match officials put a loud rattle in the ball so they had some idea where the ground was. What hope for the commentators? High up in the main grandstand, the Sky Sport commentators Grant Nisbett and Murray Mexted admitted they couldn't see anything. Their sideline eye, Tony Johnson, was immediately on the case, charging over to the far sideline where, peering into the fog, he was able to provide graphic description of what was happening down the mine. If the action was on Nisbett's side of the field, a few metres near the sideline, he would call the game; when it went to Johnson's side, the sideline eye would take over the commentary. It worked perfectly, with the trio provide a funny, inventive and somehow informative call of the game. Many would have got flustered. They didn't. When the commentary team remarked that neither side had made a line break, Johnson chimed in: "Well, none that we know of." And Nisbett announced that the Crusaders had triumphed 19-12 with: "There goes the foghorn." The following day, Johnson told me: "It was like trying to commentate on a game between ghosts." As for the most enriching Super Rugby moment, that must go to being there for the 2014 Waratahs' grand final triumph at ANZ Stadium. It was a special game, with so many champagne moments, including the last-minute kicks to win the event. For all those Waratahs followers who had suffered so much, there was at last some reward - as shown by the most startling and resounding standing ovation ever received by an Australian coach when Michael Cheika walked onto the field about 10 minutes after the final whistle. Sydneysiders are a discerning mob, but that night they headed out to the boondocks and in numbers rose as one when the Waratahs at last got it together. And with it came a feeling that maybe, just maybe, the often-teetering rugby environment had re-established a solid foothold in Australia's biggest city. Enough to even hope. © ESPN Sports Media Ltd

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Live Sports

Communication error please reload the page.

-

Football

-

Cricket

-

Rugby

-

- Days

- Hrs

- Mins

- Secs

F1 - Abu Dhabi GP

Abu Dhabi Grand Prix December 11-131. Max Verstappen ()

2. Valtteri Bottas (Mercedes)

3. Lewis Hamilton (Mercedes)

4. Alexander Albon ()

5. Lando Norris ()

6. Carlos Sainz Jr ()

-

ESPNOtherLive >>

Golf - Houston Open

Snooker - China Open

Tennis - Miami Open