|

1912

Ireland's greatest all-round sportsman?

Huw Richards

January 23, 2009

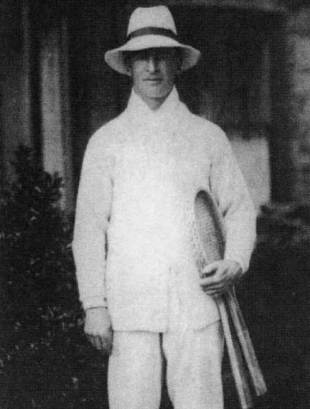

Parke won the Australian Open tennis title in 1912

© Tennis Ireland

Enlarge

Tennis star Andy Murray is hoping to follow in the footsteps of an Irish rugby player as he pursues the Australian title at Melbourne. James Cecil Parke was the winner in 1912, adding the trophy to the 20 caps he had won for Ireland at centre in the previous decade. It was a rather different event to the global competition being contested in Melbourne this week. Then it was still the Australasian championship, a moveable feast that switched between venues across Australia and New Zealand. Parke's five-set victory in 1912 over fellow-Briton Arthur Beamish took place in Hastings, New Zealand. The out of the way location may explain why reigning champion Norman Brookes, an Australian national hero as their first Wimbledon winner in 1907, had chosen not to defend his title. Parke, though, had already proved himself against Brookes, beating him in the opening rubber of the 1912 Davis Cup final in Melbourne a few weeks earlier. Parke also won the deciding match of Great Britain's 3-2 victory. Parke also won the Wimbledon mixed doubles in 1914, an Olympic silver medal in 1908 and in 1913 was claimed by one newspaper to be 'the best player in the world'. He has a claim to be Ireland's greatest all-round sportsmen - he was a scratch golfer, a fine cricketer and a chess prodigy - and is without question its best tennis player. Extraordinarily, though, there was a precedent for his dual achievement at Wimbledon and Lansdowne Road - forward Frank Stoker, winner of five caps between 1886 and 1891, also won the men's doubles in 1890 and 1893. Born in Clones in County Monaghan - the town that produced another Irish hero, the boxer Barry McGuigan - Parke was first capped for Ireland while still a student at Trinity College, Dublin in 1903. An 18-0 defeat by Wales was in keeping with the decade - arguably Wales's greatest, while Ireland fell back from the Triple Crown triumphs of the 1890s. Parke, though, was to be a fixture for the next six seasons, missing only two matches before making his final appearance in the first ever Ireland-France match in 1909. Only six of his 20 matches were won, but along with forwards Alf Tedford, George Hamlet and Frank Gardiner and wing Harry Thrift, he was part of a nucleus of durable high-quality stalwarts without whom Ireland's struggles would have been much greater. Both of his international tries, against Scotland in 1906 and England three years later, were in a losing cause, but his goal from a mark against England at Lansdowne Road in 1907 contributed to a 17-9 win.

He captained Ireland twice and it was his tackle on a Springbok that created the opportunity for an epic long-range try by white-gloved winger Basil Maclear in the first meeting between the two countries in 1906. His finest international moment, though, probably came later in the same year as one of the 13 Irishmen who held out for an 11-6 win after both of their halves had gone off injured against Wales at Belfast - one of only two championship defeats suffered by Wales in five seasons from 1905 and 1909. Nearly 40 years later E.H.D.Sewell recalled it as 'the greatest of all international victories'. He also remembered Parke, whom he picked in a 'Best Ever' Ireland XV as 'very sound and dour…if none can point to some exceptional match…certainly none can recall a game wherein he let his side down." As a portrait it sounds slightly at odds with a man with such extraordinary sporting talents, noted as a tennis player for his agility around the court. It also clashes with the view of another notable early-century chronicler, the Welsh writer Townsend Collins who remembered Parke as 'brilliant but erratic' and possessiong more 'natural genius' than the prodigious Maclear. For Collins 'he did at some time or other - and pretty often - all the good things a centre threequarter is expected to do, and some of the bad things no centre should do. He had intuition, inspiration, fire, originality ; he was a thrustful runner, difficult to tackle ; he kicked quickly and well ; and on his day was a great tackler, a successful spoiler. But often he was too impetuous ; he gave too many bad passes, and had not the cool judgment which makes the best of a wing and the most of an opportunity." Both Sewell and Collins, whose book was published in 1948, were writing as old men - Sewell in his 70s, Collins his 80s - half-a-lifetime after Parke played his last match. All such analyses are a matter of opinion, but quite such radical divergence between respected chroniclers is not an everyday matter. In this, as in just about everything else, Parke was exceptional. © Scrum.com

| |||||||||||||||

Live Sports

Communication error please reload the page.

-

Football

-

Cricket

-

Rugby

-

- Days

- Hrs

- Mins

- Secs

F1 - Abu Dhabi GP

Abu Dhabi Grand Prix December 11-131. Max Verstappen ()

2. Valtteri Bottas (Mercedes)

3. Lewis Hamilton (Mercedes)

4. Alexander Albon ()

5. Lando Norris ()

6. Carlos Sainz Jr ()

-

ESPNOtherLive >>

Boxing - Nelson v Wilson; Simmons v Dickinson; Joshua v Gavern (Metro Radio Arena, Newcastle)

Golf - Houston Open

Snooker - China Open

Tennis - Miami Open