|

Rewind to 1944

The remarkable story of French rugby's first hero

Huw Richards

December 30, 2014

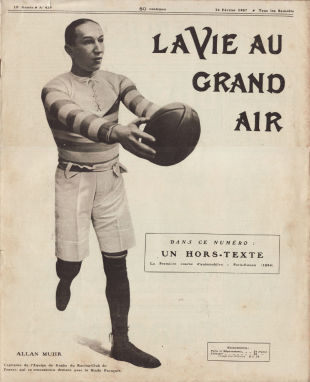

The relationship between Americans and Paris is a long and fruitful one expressed in the music of George Gershwin, the writing of Ernest Hemingway and Henry Miller, the journalism of the International Herald Tribune and most recently Woody Allen's return to film-making form in 2011. Allan Muhr, who died 70 years ago on December 29 1944, is not as famous as those listed above. But his contribution to that special relationship was as distinctive as any of them and rather more varied. His end, sadly, was as grim as any in the history of rugby, starved to death in a concentration camp at Neungamme near Hamburg. Born into a prosperous Jewish family in Philadelphia in 1882, Muhr moved to France in the early years of the last century. He appears in the 1900 US census, but made a rapid impact on his adopted homeland - although not as rapid as the one implied by sources which confuse him with the Scotsman Jimmy Muir and credit him with appearances in Racing Club's French championship winning teams of 1901 and 1903. A profile written in 1907 recorded that the newly arrived Muhr enrolled at the prestigious Lycee Janson - taking elementary French classes - purely for the purpose of playing rugby, but injured his shoulder during his first match. In spite of this setback he was rapidly a force at Racing Club, playing second row or prop and earning the nickname 'the Sioux' for his origins and distinctive profile. He evidently had the time and money necessary to devote himself to a range of sporting activities. While his professions are listed as translation and sporting journalism, he does not appear to have been encumbered by the pressing need to earn a living. That 1907 profile reported that "He amazes us because he is not the slave of any bureau chief or other boss or editor, still less of the rulers of the USFSA (the French sporting authorities of the time). He does what he pleases when he pleases." At the same time, the profile noted, he was "a slave to his passion for rugby", besides which his enthusiasms for motoring and tennis were mere pastimes. That passion was rewarded when he was chosen for France's first ever Test match - against the All Blacks on New Year's Day 1906. Muhr appears at the back of the French team picture, a skull-capped figure alongside touchjudge Cyril Rutherford, the Scot who played such a huge part in the early development of French rugby. Playing second-row alongside the French Guyanese Georges Jerome, one of two black players in the team, Muhr did well enough in the 38-8 defeat to retain his place for France's first ever match against England, on March 22 that year. France lost again, 35-8, but Muhr claimed France's first try against the old enemy, crossing after brilliant work by Stade Francais centre Pierre Maclos. He was to score again when France crossed the channel for the first time to play England at Richmond in January 1907, his effort in the corner part of a fine French comeback to level at 13-13 at half-time before subsiding before a deluge of scores from Harlequins wing Daniel Lambert, who crossed five times in all, as England ran out 41-13 winners.

That, perhaps because of a knee injury referred to in the 1907 profile, was the end of his international career. But his two tries were not equalled until the durable Marcel Communeau, the fixed point in the revolving personnel of France's early teams, claimed his second try in 1910 and not surpassed until Pierre Faillot scored a try in Dublin in March 1911 to add to the two he had claimed in France's first ever victory, at home to Scotland earlier the same year. By then Muhr was chair of selectors. He was clearly marked early for authority, refereeing the 1906 and 1907 French championship finals. His first match in charge was that historic win over Scotland. At the same time he was playing tennis well enough to reach the final of the Etretat tournament of 1909 and to become, in 1912, France's Davis Cup captain. Reprising that role in the 1920s he gave rise to one of sporting fashion's best known logos, promising player Rene Lacoste a crocodile-skin suitcase if he won a big match. The press heard the story and nicknamed Lacoste 'the crocodile', the image he later chose to represent his sporting goods business, now a significant multinational enterprise. During the First World War Muhr had served as a volunteer ambulance driver, later playing his part in the formation of the Lafayette Escadrille, a squadron of American fliers who assisted the nascent French Air Force. His collection of photographs of the Lafayette Escadrille is held by the Hoover Archive in California. After the war he continued as a major figure in rugby administration, taking part in the formation of the French Rugby Federation in 1919 and serving as its president. As a close collaborator of Pierre de Coubertin he played a significant role in France's hosting of the 1924 Summer Olympics and the first ever Winter Games in the same year. A year earlier he had played his part in the development of winter sports by attending as US delegate the founding Congress of the International Bobsleigh and Toboggan Federation (FIBT). Rugby was still an Olympic sport at this time, something he possibly regarded with mixed feelings following two brutal gold metal matches, in 1920 and 1924, between his native country and his adopted one. The USA won both, but had earlier lost to France in the final of the 1919 victory tournament of which Muhr is reported to have said that its violence was "probably the best anyone could do without a knife or revolver". When war came again in 1939, Muhr reprised his volunteer role with the Red Cross. After the fall of France in 1940 he and other Americans took refuge in Sayat in the Auvergne where the occupying authorities came to believe - and subsequent academic researchers have suggested - that they offered covert assistance to the French Resistance. Being a Jew doubtless did not help either. On November 21 he and two others were arrested by the SS, taken to the camp at Compiegne where they were interrogated, and the following May deported to Germany. He died on December 29 1944, but his services to France were not forgotten. After the war he received a posthumous award of the Legion d'Honneur - the least he merited for a life which, while it ended under unspeakably grim circumstances, was one of the most varied and eventful in rugby's annals. © ESPN Sports Media Ltd

| |||||||||||||||

Live Sports

Communication error please reload the page.

-

Football

-

Cricket

-

Rugby

-

- Days

- Hrs

- Mins

- Secs

F1 - Abu Dhabi GP

Abu Dhabi Grand Prix December 11-131. Max Verstappen ()

2. Valtteri Bottas (Mercedes)

3. Lewis Hamilton (Mercedes)

4. Alexander Albon ()

5. Lando Norris ()

6. Carlos Sainz Jr ()

-

ESPNOtherLive >>

Snooker - China Open

Tennis - Miami Open