|

England

A tribute: The remarkable story of Ronald Poulton Palmer

Huw Richards

May 5, 2015

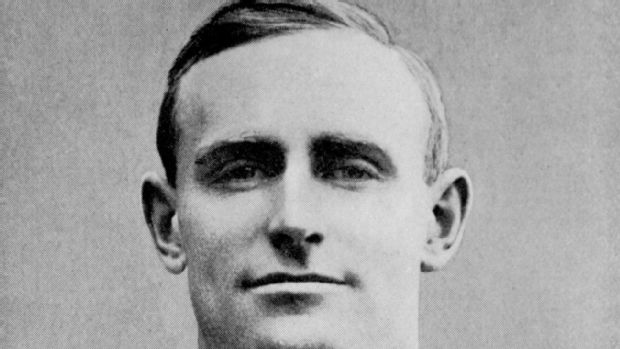

Ronald Poulton-Palmer© EMPICS/EMPICS Sport World War One took a fearful toll on rugby players. No fewer than 130 international players were killed, around six per cent of all the men who had been capped since the first match in 1871. Among those capped since 1900, the death rate rose above 10 per cent. Amid this carnage, no single death had a greater impact than that of Ronald Poulton Palmer, who was killed by a sniper's bullet at Ploegstreet Wood, Belgium just after midnight on the morning of May 5 1915. Pioneering All Black captain Dave Gallaher, killed in 1917, might contest the title of greatest player to fall on the western front. But Poulton, as he was known for all but the last few months of his playing career - changing his name in 1914 after a huge inheritance, including a substantial holding in the Huntley and Palmer biscuit empire, from an uncle named Palmer - was the undoubted star. He was the most vivid presence in some of the most exciting teams to have played rugby, and also somebody likely to have made a serious impact off the field had he survived the war. As such he ranks alongside the poet Rupert Brooke - his centre partner in the Rugby XV of 1906, who died two weeks earlier - as an exemplar of the 'Lost Generation' of talent and promise destroyed by the war. Poulton had ended peacetime as England's captain, leader of a team which completed a second consecutive Grand Slam with a 39-3 win in Paris in which he scored four tries. He had played 17 times for England, his 14 wins an all-time English record shared with his almost equally brilliant team-mate, the back rower 'Cherry' Pillman. He had been for some years a mesmeric presence on the field. A Welsh opponent asked "How can one stop him when his head goes one way, his arms another and his legs keep straight on?" The writer AA Thomson recorded that his bodyswerve was so subtle that "you had the optical illusion of seeing him go, not past the full-back but right through" while spectators behind the posts "declared that it was the defenders trying to tackle him who appeared to swerve out of the way". All of this served to give him what the astute Welsh observer Townsend Collins called "a quality of unexpectedness which played havoc with the defence". And not just with opposition defences. One team-mate recalled "Hanged if I ever knew where he was going".

That sheer unpredictability caused an early, brief career setback. Hailed as Rugby's best all-round sportsman in half a century, he was assumed to be a certainty for a blue at Oxford but was left out of the 1908 Varsity match because team-mates were as confounded as opponents. He played for England before he won his blue, making his debut against France at Leicester in 1909 before making up for lost time in that year's Varsity match by scoring five times - a record for the fixture - in the demolition of Cambridge. Poulton played club rugby for Harlequins, where the freethinking Adrian Stoop shared none of the qualms of the Oxford selectors, and was a fixed point in England teams in the highly successful years running up to the war. His star quality was recognised elsewhere - placards in Cardiff in 1913 proclaiming 'Come and see RW Poulton'. Wales doubtless felt they saw all too much of him as he ran amok on a foul Arms Park morass that should in theory have restricted him, set up a try for Pillman and found about the only patch of dry land in the ground from which to launch a drop-goal. England won 12-0. He had the glamour associated with privilege and 'effortless excellence', once turning up for a match against Wales on an overnight train from the Alpine ski slopes. And there was privilege in his background. His father was Edward Poulton, an Oxford professor and a biologist of achievement sufficient to sit alongside his son in the national Valhalla formed by the Dictionary of National Biography. The writer and economist Peter Jay, a relative, has recalled as child visiting the family home in Oxford with its staff of several servants. His uncle's bequest made him independently wealthy. But playboys tend not to study engineering, the discipline Poulton read at Oxford in preparation for a likely career with Huntley and Palmer. They are even less likely to have best friends like William Temple, destined to become Archbishop of Canterbury, who recalled him as having "wonderful buoyancy and freedom from self-consciousness' and 'a genius for evoking affection". Least of all are playboys likely to leave bequests to the Workers Education Association, an expression of the thoughtful, questioning attitude which in 1912 led him publicly to criticise the RFU's rigid application of the rules on professionalism as likely to exclude working-class players, protesting that "rugby is too good a game to be confined to any particular class."  Ronald Poulton-Palmer© Barratts/EMPICS Sport Trained as a territorial before the war, he joined up on its outbreak and after officer training was sent with the Royal Berkshire Regiment to the front in 1915. There was extraordinarily to be one final match, recorded by his biographer James Corsan as the first ever "in a military forward area, within range of the enemy's guns". On April 14 Poulton led a 48th Division team, including 11 Gloucester players and two other internationals, to a 17-0 win over a 4th Division team including five internationals. The referee was Basil McLear, a legendary Irish threequarter, and after two halves of 25 minutes each way the players returned to military duties. Three weeks he later he was dead. The odds must be, as Graham McKechnie, the BBC journalist who compiled an excellent documentary about his life in 2008, has suggested, that even had he survived he was unlikely to have returned to rugby after the war. He would have been 30 by the time of the first post-war Five Nations, almost certainly with serious responsibilities at Huntley and Palmer. Had he lived he would very likely have been a major figure in Reading, a town dominated by the biscuit company, and beyond. It is not hard to imagine him as a significant figure in national business and possibly politics into the 1950s, and potentially as a liberalising influence on the amateur fundamentalism which was to become one of rugby's afflictions. But that inevitably remains conjecture. What he did do in his 25 years was enough to inspire two substantial biographies - one in 1919 by his father, a volume weighted by paternal grief and piety, and Corsan's authoritative For Poulton and England (2008). He came too early for any film record to exist. But the words of those who saw him play mean that, a century after his death, he remains one of the most vivid figures in rugby history. © Huw Richards

|

Live Sports

Communication error please reload the page.

-

Football

-

Cricket

-

Rugby

-

- Days

- Hrs

- Mins

- Secs

F1 - Abu Dhabi GP

Abu Dhabi Grand Prix December 11-131. Max Verstappen ()

2. Valtteri Bottas (Mercedes)

3. Lewis Hamilton (Mercedes)

4. Alexander Albon ()

5. Lando Norris ()

6. Carlos Sainz Jr ()

-

ESPNOtherLive >>

Darts - Premier League

Golf - Houston Open

Snooker - China Open

Tennis - Miami Open