|

Comment

An artist on the field, a poet off it

Huw Richards

August 30, 2013

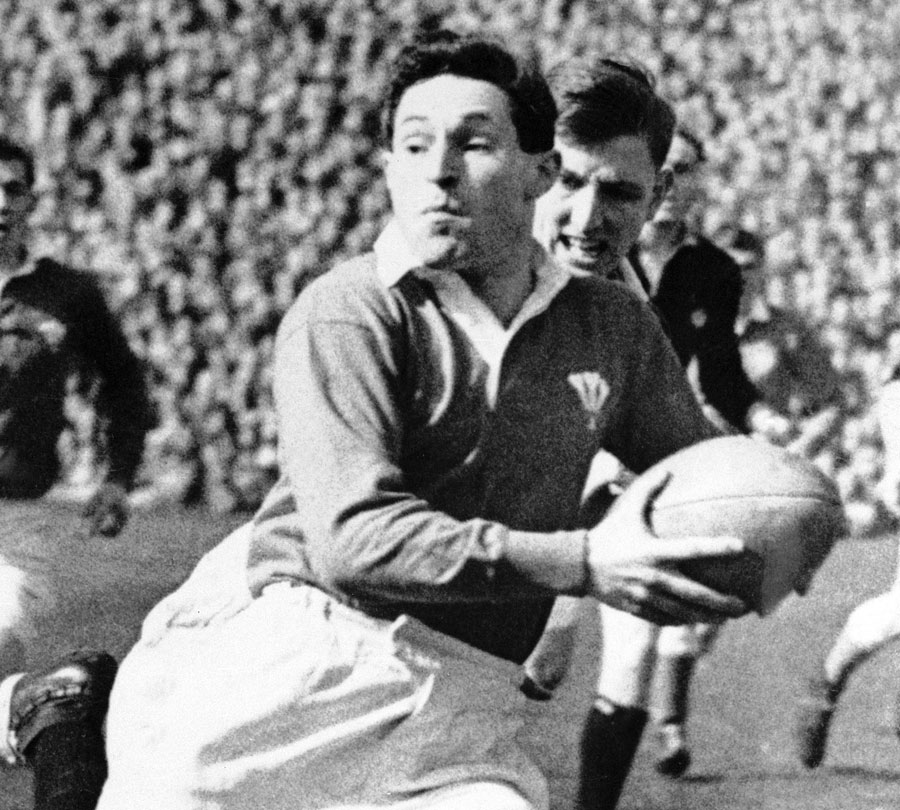

Cliff Morgan won 29 Wales caps - a record for an outside-half until broken by Neil Jenkins in 1996 © PA Photos

Enlarge

So now there are three. The death of Cliff Morgan leaves only Gareth Griffiths, John Gwilliam and Courtenay Meredith as survivors of the last Wales team to beat the All Blacks, almost 60 years ago in December 1953. All were fine players. Griffiths and Meredith played in the Test team for the 1955 Lions, the best of that time. Gwilliam's teaching responsibilities robbed him of a shot at the Lions - and quite possibly the captaincy - five years earlier but he retains to this day the distinction of being the only Welsh captain to lead two winning teams at Twickenham. They were members of a terrific team, among whose departed members Bleddyn Williams and Ken Jones count among the game's true giants. But not even they made more of an impact than Cliff. He was, as Scots were once wont to say, 'a man of parts'. His greatness as a rugby player is not in question, and he added accomplishment and achievement as both broadcaster and broadcast executive.

The Welsh members of the 1955 Lions pose at Heathrow prior to their departure - From left to right, top to bottom - Alun Thomas and Haydn Morris; Cliff Morgan and Trevor Lloyd; Courtenay Meredith and Brin Meredith; Billy Williams and Rhys Williams; Russ Robins and Clem Thomas

© PA Photos

Enlarge

He means something a little different to each generation. To the middle aged he is the voice on the television soundtrack of one of the game's iconic moments, the length-of-the-field Barbarians counterattack leading to Gareth Edwards' try against the All Blacks at Cardiff in January 1973. To our fathers he was the most vivid rugby presence of the 1950s - appropriately, given his later involvement with the medium, the first generation of players whose exploits were brought to a wider audience by television. To those younger he was the benign radio interviewer eliciting insights from former stars in 11 years (1987-98) of the gently nostalgic Sport on Four. Most of all he was, as Dai Smith and Gareth Williams point out in the most brilliant passage of their incomparable Fields of Praise, at once the most beguiling and most representative of Welsh archetypes - the Valleys-born miner's son who grew up in a bilingual, chapel-going, hymn-singing matriarchal household and developed into 'the identikit Welsh outside-half'. Diminutive - 5ft 7in - lethally fast off the mark and a taker of calculated risks, he was an individualist who as Griffiths recalled 'would always look to see if there was anything he could do. If there was, you knew he'd have a go - and he'd go like bloody lightning'. Like many great Welsh players he benefited from the mentoring of an outstanding teacher, in his case Ned Gribble at Tonyrefail Grammar School. Cliff progressed from the Wales Secondary Schools team in 1948 to his debut for Cardiff at Northampton a year later, and within two years more to a full Wales cap. By the time he retired in 1958 he had played 202 times for Cardiff and won 29 Wales caps - a record for an outside-half until broken by Neil Jenkins in 1996 - as well as playing all four Tests, one as captain, when the Lions toured South Africa in 1955. Though a time of vast crowds, it was not one of intrinsically exciting rugby - endlessly punctuated by scrums, lines-out and handling errors, dominated by spoiling back rows who denied creative players space and time in horribly crowded midfields. Cliff spent his career, as Smith and Williams wrote 'endlessly working for the extra half-yard of space'. It was the manner in which he sought it that made him so compelling, his appeal beautifully caught by the great New Zealand writer Terry McLean after watching him in the victories by Cardiff and Wales over the 1953 All Blacks: "Cliff Morgan to me was just a schoolboy, delighted to find that he could sidestep and weave and dodge, happy because he could gather a rolling ball at top speed and kick it back over his shoulder, and imbued all of the time with the feeling that rugby was the grandest fun in the world". But accompanying that infectious sense of enjoyment was the cool craftsmanship of a man capable of controlling an international match with his tactical kicking, as he did on a foul day at Twickenham in 1958, and of putting in the defensive stint essential to Cardiff's win over the All Blacks. He played in a prosperous time for Welsh rugby. As well as beating the All Blacks, Wales won at least three matches out of four in each of his first five full seasons in the team, but like Ireland in the 2000s were wont to lose one a year - as they did in his year as captain, 1956, when the title was shared with France. So there was only one Grand Slam, in 1952, but four titles (two shared). His career arguably peaked with the Lions in South Africa, where his style proved perfect for the hard grounds and his combination with England centre Jeff Butterfield produced some of the best rugby yet seen from a Lions team and a 2-2 draw with the Springboks. Off the field he was, as JBG Thomas wrote 'the radioactive particle around which the whole social side of the tour revolved', conductor of a choir which began the process of beguiling South Africans from the moment of the team's arrival, standing on the plane staircase to sing traditional Afrikaaner melody Sarie Marais.

His was a very different rugby world. There were no leagues and no trophies - his one tangible prize came in a sabbatical in Ireland when he won the Leinster Cup with Bective Rangers. He gave up rugby in 1958, leaving a tour of New Zealand and playing for Wigan as unfulfilled dreams, because he could no longer afford to play. That trip to New Zealand was within his grasp - he would certainly have gone, quite possibly as captain, with the 1959 Lions and Lord Wakefield made a personal appeal to him to stay on. But far from being a reason to carry on, the prospect of another six months away from work while he toured was one of the factors in quitting when he did. Instead he went into broadcasting, a path trodden since by many stars in rugby and other sport. In some cases that leads to what might be called Shearer Syndrome, 10 years of playing a sport very well leading on to 20 well-rewarded years of talking about it very badly. Cliff was not remotely like that. He knew he owed his opportunities and much else to rugby, saying that "I owe everything to rugby. It gives you a sense of proportion, of understanding people, of fair play and discipline - which is the most important thing in broadcasting, in rugby and in life generally". But he was also a natural broadcaster, with a marvellous voice and a poet-like sense of the right word. Has any player produced a better, simpler appreciation of a team-mate than his description of Cardiff and Wales scrum-half Rex Willis as 'my better half'? He went into management, editing the BBC's Grandstand and the ITV current affairs show This Week and rising in the BBC hierarchy to become Head of Outside Broadcasts from 1976 to 1987. Rugby helped not only in televising the Five Nations but when it came to royal events - the Queen's then secretary Philip Moore had played alongside him for the Barbarians in 1951. He recovered remarkably from a stroke in 1972 which, among other inflictions, left his voice slurred. Yet within a year he was producing that immortal accompaniment to the Edwards try. That his voice was later destroyed again by cancer of the larynx was one of life's random cruelties. He had been unwell for a long time, so his death after a full life does not leave the sense of shock that accompanied the premature passing of his contemporaries and outside-half rivals Glyn Davies and Carwyn James. But as a cherished part of Welsh national consciousness for more than 60 years, his death leaves many of us feeling that much older and a little sadder.

© ESPN Sports Media Ltd

| |||||||||||||||

Live Sports

Communication error please reload the page.

-

Football

-

Cricket

-

Rugby

-

- Days

- Hrs

- Mins

- Secs

F1 - Abu Dhabi GP

Abu Dhabi Grand Prix December 11-131. Max Verstappen ()

2. Valtteri Bottas (Mercedes)

3. Lewis Hamilton (Mercedes)

4. Alexander Albon ()

5. Lando Norris ()

6. Carlos Sainz Jr ()

-

ESPNOtherLive >>

Golf - Houston Open

Snooker - China Open

Tennis - Miami Open