|

1964

Welsh rugby's turning point

Huw Richards

June 18, 2014

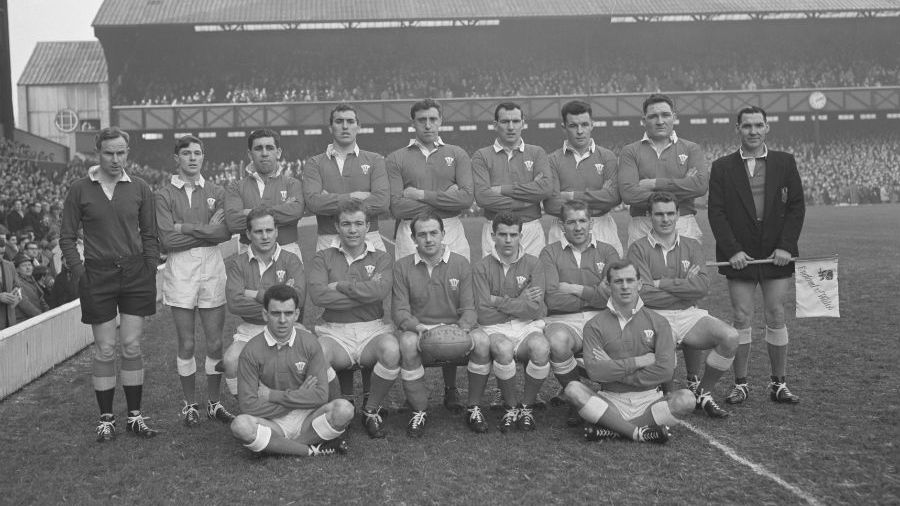

The 1964 Welsh vintage © PA Photos

Enlarge

Half a century on, the memories remain vivid. So when Clive Rowlands sits in front of his television on Saturday afternoon to watch Wales play South Africa, he will inevitably think back to the day in 1964 when he led Wales against the Springboks in their first southern hemisphere Test. It jostles with plenty of other memories. Few rugby lives have been fuller. As well as leading Wales to the Triple Crown in 1965, Rowlands has a triple distinction to himself - not only captaining and coaching Wales, but becoming president of the Welsh Rugby Union. And at 76 his enthusiasm is undimmed. He's as keen to talk of the rugby of today - of the range of matches to be consumed via television at the weekend, the talent of Matthew Morgan and the promise of his own teenage grandson Tiaan Jones - as he is of the great games and players of the past. To look back half a century is to remember another world. It was almost the last time sporting contact with apartheid-era South Africa would be fairly uncontroversial. Basil D'Oliveira had just made his debut for Worcestershire - his first England cap was still two years away. Nelson Mandela, though on trial for his life, was little known outside South Africa. Rowlands remembers the attempt by Monmouthshire County Council to first deny himself, Alan Pask and Brian Price leave to go on tour, then to refuse paid leave as an early straw in that particular wind. "In the end they had to pay us, since it said clearly in our contracts that we were to be paid while on service for county or country." He was and is a thoughtful and perceptive man with left of centre views. He had seen South Africa as a Wales schools tourist in 1956 and recalls spending much of his time talking to the hotel caretakers about the reality of non-white lives in South Africa. But boycotts, either personal or collective, were a thing of the future :"All I wanted to do was play for Wales against South Africa." Touring, except in the very different sense of alcohol-fuelled Easter jollies to the west country, were a novelty for most. A decade earlier New Zealand had invited Wales to visit, but the invitation was vetoed by the International Board, keen to preserve the Lions' monopoly of test touring. That monopoly was finally broken when Scotland were allowed to visit South Africa in 1960. But Wales had to wait until 1964 for their first turn. "It was new to almost everybody. Dewi Bebb, Ken Jones, Alan Pask and Haydn Morgan had been to South Africa with the Lions in 1962 and the assistant manager Alun Thomas had been there in 1955, but that was it."

That inexperience extended to the Welsh Rugby Union which accepted a ridiculous itinerary. "We went out via Nairobi, where we played East Africa. Then we went to the Cape to play Boland and three days after that we had the Test match in Durban, before going on to North Transvaal and Orange Free State. It was crazy to play the Test after just a couple of warm-up games. It should have been at the end, giving us more time to adjust." And it was not just a matter of South Africa conditions and opponents that required acclimatisation: "We also had new rules. The length of the line-out was set by the team with the put-in, where previously you would place the open side directly opposite their outside-half. Everybody not involved had to stand 10 yards back. And there were other changes as well. The WRU put on a couple of practice games for us before the tour, but there's no way that could prepare you for playing against South Africa." South Africa were keen to greet Wales. "All of them - New Zealand, Australia, South Africa - wanted to play Wales. When I'd been there in 1956 all I'd heard about was the Lions tour the year before. And it wasn't the Boks they talked about, but the Lions and above all Cliff Morgan." And the side they greeted was a good one. "We'd had a good season. While we lost to the All Blacks 6-0 we'd been unbeaten in the Five Nations and shared the championship with Scotland." The historical misfortune of players from this time has been to have been obscured retrospectively from view by the brilliant teams who followed in the 1970s. "There were some brilliant players - people like Keith Bradshaw and Ken Jones in the backs, great back rowers like Dai Hayward and Alan Pask, Brian Thomas and Brian Price who were both hard men and very good players. If they'd played under the rules we had a few years later we'd still have been talking about them." But the South Africans were also very good. "They were better than the All Blacks of 1963, with quality all the way through. Lionel Wilson was a classy fullback and Jannie Engelbrecht was a real flier on the wing. In the centre you had John Gainsford who was big and could run and could side-step. They had a lovely pair of full backs - Keith Oxlee, who was at his best, and Nelie Smith."

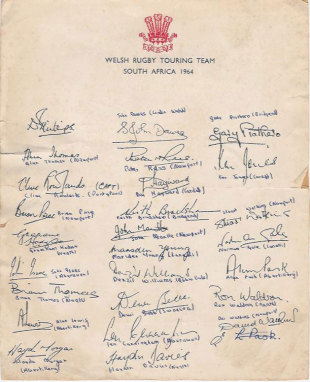

An autograph sheet signed by the welsh tourists

© Scrum.com

Enlarge

And, typically for the Boks, there was a formidable pack: "That was some back row - Tommy Bedford, Doug Hopwood and Frik du Preez. The size of them! And they could play. Frik played open side. He was huge, but he could run, and do everything else. There was Hannes Marais and Myburgh, the 18 and a half stone prop and Malan, who'd been captain in 1960." In steaming heat on May 23, 1964 at King's Park, Durban - the ground Wales returned, for the first time since, last Saturday - Wales held their own well into the second half. At three-quarter time it was still 3-3, with a Bradshaw penalty cancelling out one by Oxlee. But Wales were holding on rather than looking likely to score again themselves. "We were under increasing pressure and it was incredibly hot. With about 20 minutes to go I looked at Len Cunningham, our loose-head prop, and got a real shock because his shorts had turned pink. We were wearing heavy cotton shirts and with all the sweat coming off us in the heat, the colour had run. I looked round at the rest of the pack and the same had happened to them. And you didn't drink water during the game, because it was thought you'd get colic." It was a drop goal which broke Wales's resistance. "Grahame Hodgson missed a kick to touch, Wilson caught it and dropped a goal from 45 yards. We'd done so well and were exhausted and you thought 'bloody hell …" The floodgates opened and tries from Marais, Hopwood and Smith plus three conversions and a penalty from Oxlee came in the last quarter. A final score of 24-3 might not look much by modern standards, but was Wales's heaviest defeat since 1924. "We had everything against us. There was the heat and the new rules. We didn't have a coach. As captain I had to do that. There was no doctor or physio. There was a local referee. But with all of that the main difference was that they were better than us." Much of the subsequent press criticism was brutal. Some lessons were not learnt, as Rowlands found to his cost. Five years later, as coach, the WRU's fixture planners lumbered him with an even dafter schedule for Wales's first short tour of New Zealand. Twenty-five years later, as president, he saw the WRU savagely divided when leading players, facilitated by union officials, accepted invitations to play in matches celebrating then by-then long-isolated South African union's centenary. But the on-field lesson of the 24-3 defeat was taken on. Rowlands sat, with Pask, journalist JBG Thomas and leading WRU officials on an advisory committee to look into standards of play in Wales and the possible benefits of coaching. In helping persuade the committee that coaching must be accepted in Wales, Rowlands was also mapping out his own future as he became national coach in 1968 and presided over the brilliance of the first half of the 1970s. Looking back, he is in complete agreement with Dai Smith and Gareth Williams, the authors of the still incomparable WRU centenary history Fields of Praise, when they argue that an intolerably hot afternoon in Durban was one of the most important days in Welsh rugby history. "There's no doubt about it. It was the turning point. Everything that happened after that started in 1964." © ESPN Sports Media Ltd

| |||||||||||||||

Live Sports

Communication error please reload the page.

-

Football

-

Cricket

-

Rugby

-

- Days

- Hrs

- Mins

- Secs

F1 - Abu Dhabi GP

Abu Dhabi Grand Prix December 11-131. Max Verstappen ()

2. Valtteri Bottas (Mercedes)

3. Lewis Hamilton (Mercedes)

4. Alexander Albon ()

5. Lando Norris ()

6. Carlos Sainz Jr ()

-

ESPNOtherLive >>

Golf - Houston Open

Snooker - China Open

Tennis - Miami Open