- Rewind to ... 1974 Emilio Medici Grand Prix

Bernie's busman's holiday to Brasilia

Laurence Edmondson November 25, 2011

- Drivers:

- Bernie Ecclestone

- |

- Emerson Fittipaldi

- |

- Arturo Merzario

- |

- Jody Scheckter

Brazil's love affair with Formula One dates back to the early 1970s, when popular interest was sparked by Emerson Fittipaldi's championship successes and fuelled by the introduction of a Brazilian Grand Prix on the calendar. Originally a non-championship race in 1971, the event was added to the official calendar in 1973, with the old 5-mile layout of Interlagos circuit acting as a formidable host.

The race in late January immediately proved a hit with the F1 paddock, dovetailing nicely with the traditional season opener in Argentina while offering two weeks of sun in South America during Europe's coldest month. F1 folk would regularly embrace their Latin hosts' party spirit, and driver biographies are full of tales of booze-fuelled revelry between the races.

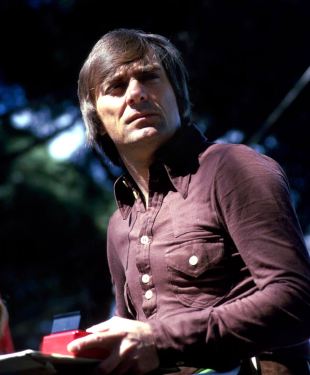

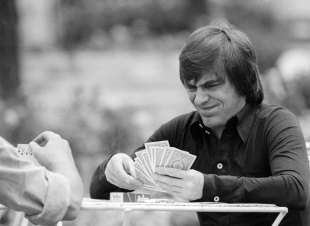

In 1974 the party was extended for yet another week with the introduction of a one-off, non-championship race in Brasilia. The military dictatorship was keen to bring the vibrant sport to the country's capital city, and the teams - minus Ferrari, Lotus, Shadow and Hill - were happy to cash in on the offer of an extra race. The deal with the Brazilian government was facilitated by local superstar Fittipaldi, but the teams' terms were negotiated by Brabham boss Bernie Ecclestone.

For President Emilio Medici the race was an opportunity to paint Brasilia - a purpose-built and somewhat detached capital city founded in the 1960s - as a genuine rival for the economic and cultural centres of Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, while creating yet another distraction for his regime's more sinister dealings.

For the teams the race was the last stop on that year's South American adventure, which had involved the Argentine Grand Prix, won by Denny Hulme, the Brazilian Grand Prix, won by Emerson Fittipaldi, and a test at Interlagos, which to the other astonishment of the other teams was topped by the hardest partiers of them all: James Hunt and the Hesketh team.

Viewed from the air, Brasilia's streets resemble the outline of an aeroplane and the newly-constructed Autodromo Emilio Medici could be found nestled under the northern-most wing. It was part of a wider multi-million dollar sports complex, including a football stadium and a gymnastics venue, all built in the modernist architectural style of the surrounding government buildings. But it was a 600-mile trip from Sao Paulo to Brasilia and in the end only 12 drivers signed up to the extended stay, meaning the grid was half the size of the one at Interlagos the previous weekend.

Those that made the effort were suitably rewarded as the travelling paddock was put up in a huge luxury hotel courtesy of Ecclestone. In Susan Watkins' biography of F1's supremo, John Hogan, who worked for McLaren's title sponsor Marlboro at the time, described how the paddock was taken care of.

At the time Brasilia was in the media spotlight as British police attempted to extradite Ronnie Biggs - of great-train-robbery fame - back to the UK following his escape from prison in 1965. It was no secret that Biggs was in Brasilia in early 1974, with the British press reporting that he was being held in a prison "fitted out like a top-class hotel", but Hogan recalls that Biggs was in fact staying in the very same hotel as the F1 teams!

A passage from Watkins' book Bernie reads: "While the Formula One team members were sitting about the hotel someone shouted out 'Hey Bernie, there's a bloke down in reception wants to see you and his name is Biggs.' Although Bernie says that he has never met Ronnie Biggs, he played along, shouting in return 'What a bastard, he owes me a tenner!' Several years later outlandish rumours linked Ecclestone to the great train robbery, but there was no proof and a couple of papers were sued as a result. Ecclestone later told the Independent that he got to know getaway driver Roy James long after the event, adding "There wasn't enough money on that train; I could have done something better than that."

When the teams finally got down to business in Brasilia they were met with wet weather during the first practice session, but it was still clear that only four drivers were going to be competitive: Emerson Fittipaldi in the McLaren M23, Carlos Reutemann in the Brabham BT44, Jody Scheckter in the Tyrrell 006 and Carlos Pace in the Surtees TS16. Wilson Fittipaldi, Emerson's brother, rented a Brabham from Ecclestone for the event, but struggled to get the BT44's handling to his liking and was off the pace of team-mate Reutemann.

Perhaps of greater interest was another Brazilian driver at Brabham that weekend. A 22-year-old Nelson Piquet befriended the team's mechanics and was bundled into the boot of their hire car to get him into the circuit for free. In return he polished the BT44s all weekend and worked as a humble runner. Just four years later he was behind the wheel of a Brabham in a grand prix and by 1981 he'd won the team's first title under Ecclestone's ownership.

The second practice session was dry, allowing the cars to lap roughly six seconds faster and the drivers to get their first proper taste of the bizarre little circuit which many compared to a go kart track. Reutemann secured pole with a 1:51.18 ahead of Emerson Fittipaldi (1:51.27), Scheckter (1:51.40) and Pace (also 1:51.40). But despite the top four being split by just 0.22s, the rest of the field was way off the pace with Arturo Merzario's Williams a further two seconds adrift in fifth. The biggest disappointment was Hunt, who was hoping to drive the new Hesketh 308 he had tested at Interlagos earlier in the week but due to a cracked fuel tank had to settle for a year-old March 731 with a dodgy clutch. He was 13 seconds off the pace.

Ten cars made the finish but on the whole it had been a rather drab affair, especially in comparison to the Brazilain Grand Prix at Interlagos the previous weekend. With no championship points on offer, the travel-weary teams lacked interest and excessive front tyre wear from an unusually abrasive surface led to frustrating levels of understeer for most of the drivers. Scheckter, however, showed no shame in his lack of commitment: "There is a corner in the middle of the circuit that I think can be taken flat," he said. "I think in a real [championship] GP I would make it flat, but in this race I was not really interested in trying."

After the race Scheckter, Fittipaldi and Merzario were given the dubious honour of receiving a trophy from Medici, who took great pleasure in having a Brazilian on the top step of the podium. But for many observers the race was nothing but fluff to draw attention away from the Medici regime's darker secrets, which involved torture and strict censorship of the press.

Six weeks later Medici lost the 1974 Presidential election, albeit to a member of his own party, Ernesto Geisel, who had been handpicked to become his successor. Geisel slowly eased the country towards a more democratic system, although there would not be another truly free election in Brazil until 1989.

Formula One's popularity in Brazil continued to grow regardless, with the championship grand prix becoming a mainstay on the calendar. However, Brasilia never hosted another Formula One race and the circuit - renamed Autodromo de Brasilia soon after the inaugural race and Autodromo Nelson Piquet in 1995 - has only been used for national events since.

© ESPN Sports Media Ltd.

Laurence Edmondson is deputy editor of ESPNF1 Laurence Edmondson grew up on a Sunday afternoon diet of Ayrton Senna and Nigel Mansell and first stepped in the paddock as a Bridgestone competition finalist in 2005. He worked for ITV-F1 after graduating from university and has been ESPNF1's deputy editor since 2010

Laurence Edmondson is deputy editor of ESPNF1 Laurence Edmondson grew up on a Sunday afternoon diet of Ayrton Senna and Nigel Mansell and first stepped in the paddock as a Bridgestone competition finalist in 2005. He worked for ITV-F1 after graduating from university and has been ESPNF1's deputy editor since 2010